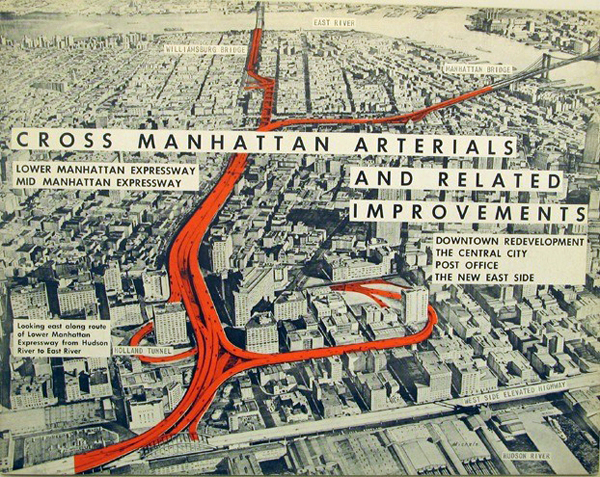

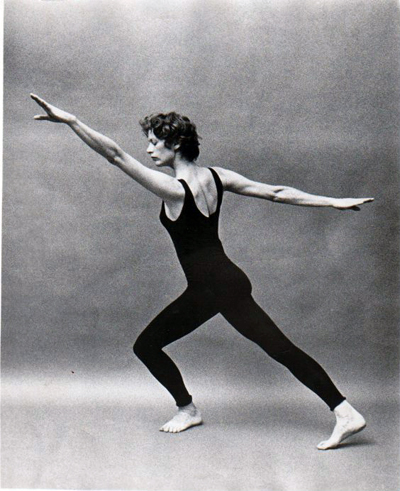

The other day, I had the pleasure of interviewing Julie Finch (formerly known as Julie Judd), dancer, choreographer, activist, and founding mother of SoHo. In 1969, with the help of her late ex-husband Donald Judd, Finch co-founded Artists Against the Expressway, a group of activist-artists that included Robert Rauschenberg, Louise Nevelson, and Frank Stella, among others. The group opposed Robert Moses’ plan to build the Lower Manhattan Expressway, a ten-lane elevated highway that was to run across Broome Street, thereby razing the then-thriving SoHo artist community. Needless to say, the Expressway was never built, and that’s thanks in part to Finch’s efforts.

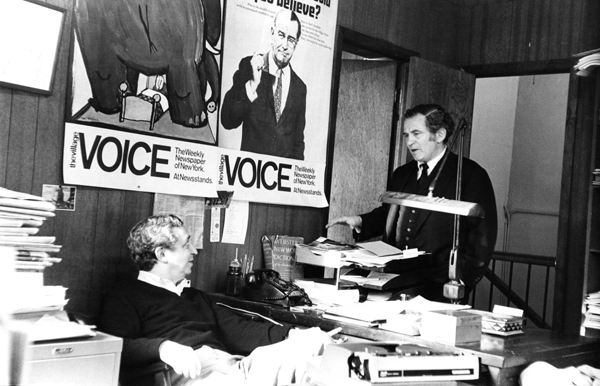

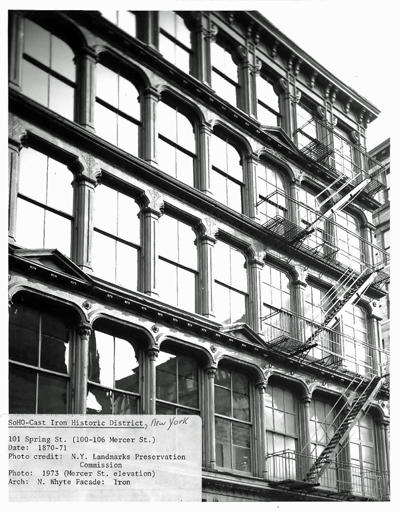

I asked Finch how Artists Against the Expressway came to be, and she traced it to an article by Mary Perol Nichols in the Village Voice about mounting opposition to the Expressway, which would be one block from the building they would be moving into later that year at 101 Spring Street in SoHo. (The building is currently home to Judd Foundation.)

Before reading Nichols’ article, Finch’s husband had written a letter to Mayor Lindsay that opened, “I thought that one of your campaign promises was that the Lower Manhattan Expressway would never be built.” The letter went on to list a slew of reasons why the Expressway should not be built. After the Voice article appeared, Finch phoned Nichols, who invited her to a meeting of a citywide coalition against the Expressway at the Lower East Side Neighborhood Association that included groups representing many downtown neighborhoods. She describes the meeting as such:

So I went down there. I probably had my baby in the stroller. The social worker there was named Joan Wager and so she said, well, can you help organize the artists? And I said, “Well, I’m only a mom. You know, I’m not really good at that.” And she said, “That’s okay, I’ll help you. You can do it.” She social worked me!

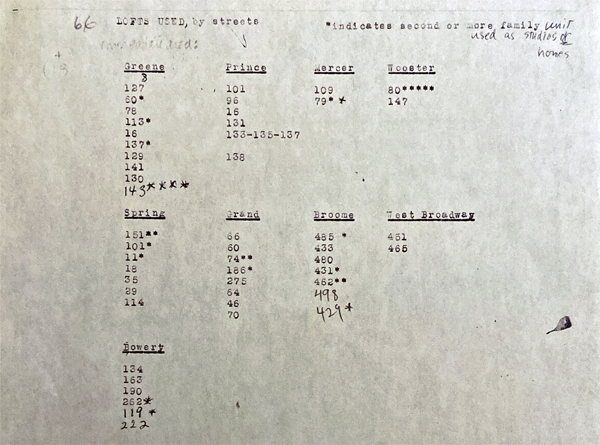

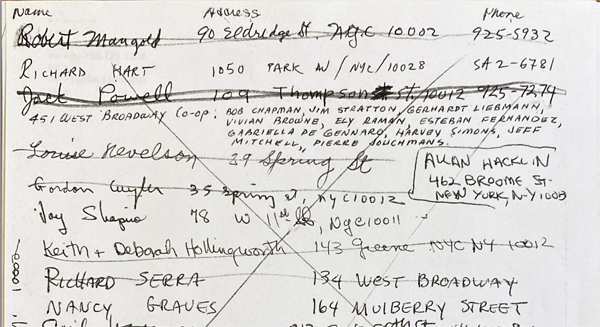

Finch set about making lists of the artists who lived in co-ops and the artists who were renting to demonstrate what would be lost by building the Expressway. She attended more meetings, and testified at public hearings about the importance of artists to the cultural life and economy of New York City.

“I remember going to one of those meetings and this man, I don’t remember his name right now, but he was a little condescending because I was just a young mother, you know?” Finch recalls. “And he said, well, maybe your husband could make us posters. And I said, I don’t think that he would be suitable because he’s an abstract artist. And it was kind of condescending that he thought artists are only good for making posters.” Whatever his name, this man severely underestimated the power of artists, and mothers.

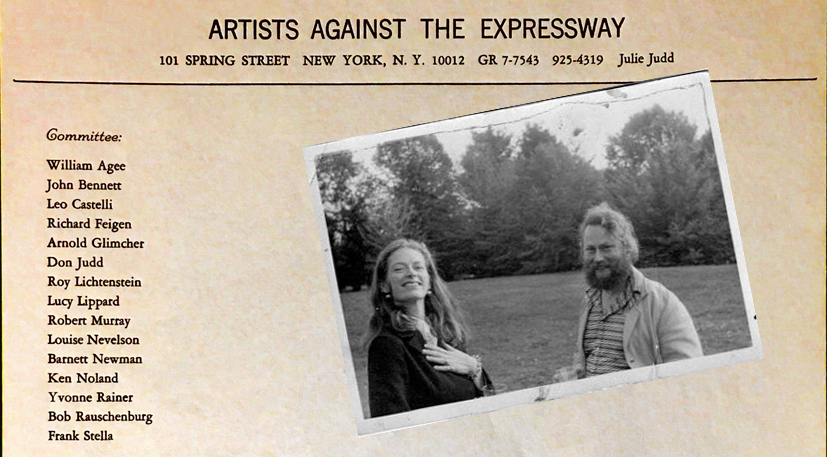

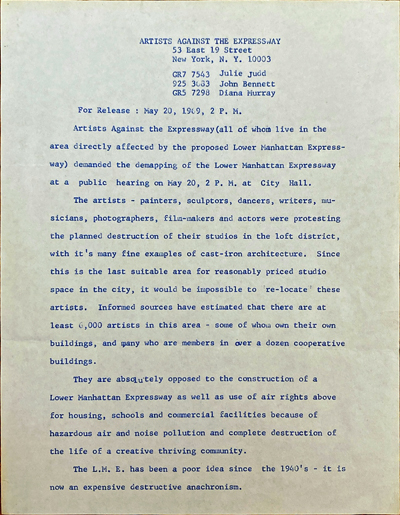

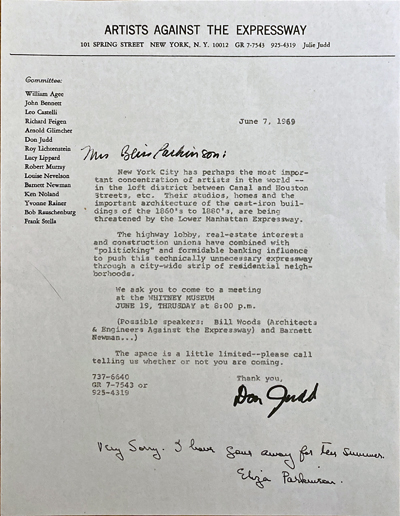

Finch and her cohorts actually did make posters for a public hearing organized by Percy Sutton, Manhattan Borough President, and she also had stationery printed, making it all official:

Richard Feigen got involved, his gallery was on Greene Street and he suggested that I should, when we were still living on 19th Street, that we should make stationery and that we needed a committee list you know? Looking back on it now, I was completely, I don’t know what, not naive, but I did not know how powerful I was because Don Judd was well known. So I just called up all these people and said, could you be on the committee please? And they all said yes, so the committee was kind of startling. I went to a local printer near 19th Street and he printed up the stationery and that was kind of exciting. We had art dealers on there. We had artists, we had my friend Yvonne Rainer.

At one of the meetings, Finch met Wilbur (Bill) Woods, a Greenwich Village resident and prominent city planner, from the group Architects and Engineers Against the Expressway. “He was fantastic,” Finch says. “In one of the hearings he said, quoting Scientists against the Expressway, that you build a 10-lane highway, a super highway, the traffic will all be stuck and there’ll be tons of pollution because the cars and trucks will be waiting to get into the two lane Holland Tunnel.” It was around this time that Percy Sutton called another public hearing where he mentioned an alternative plan, where the Expressway would loop around the southern tip of Manhattan instead of cutting across Broome Street.

Finch adds that in May 1969, Norman Mailer, who was running for Mayor that year, “testified that the Expressway was a project that will further poison our city, eliminate nearly a hundred thousand jobs, displace thousands of residents, and most importantly, destroy the communities that lie in its path.”

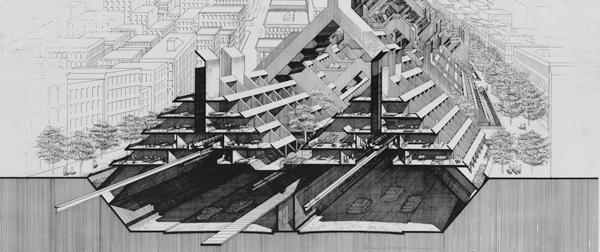

Despite all of the opposition to the Expressway from diverse factions, as well as a viable alternative plan, there were others who wanted to push it through, including David Rockefeller and his Downtown-Lower Manhattan Association, and, of course, Robert Moses, as well as powerful downtown business interests, the Automobile Club of New York, and the city’s construction workers’ union.

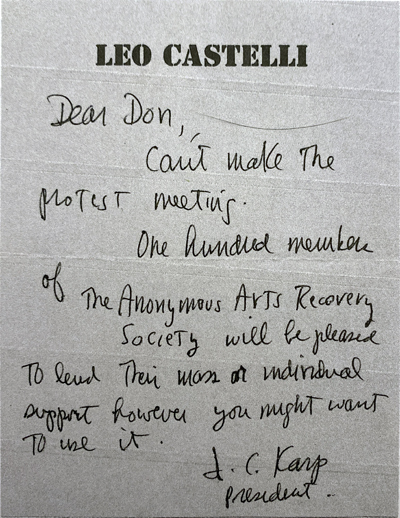

In early June, Artists Against the Expressway called a meeting of their own. Finch recalls:

I was slightly oblivious to the amount of power that I had available to me as the wife of a well-known artist. So I called up the Whitney and said, could we have a meeting there? And [they] said, of course you can! Oh, first I called the Modern. And they said, well, we’ll think about it. And then they said, we can’t because there’s a conflict because of the Rockefellers. They didn’t mention their names, but because of the wealthy collectors. So the Modern said no. Then we called the Whitney and they said, of course you can have a meeting here.

On June 7, Finch and her husband sent out invitations to the meeting to a long list of artists and urbanists and asked those living outside of New York to write to New York City Mayor John Lindsay. Finch recalls her husband’s letter writing campaign:

And Don, he wrote to all these museums, across the country and around the world saying can you please write to the Mayor saying this Expressway is a terrible idea. The artists depend upon their loft working spaces. The museums were in Amsterdam and Hamburg, the Walker Art gallery Gallery in Minnesota, the Corcoran Gallery of Art in DC, and the Fort Worth Arts Center, as well as the Detroit Arts Institute, City Art museum of St. Louis, and others. And then Artforum wrote a long letter.

And then on June 19, Finch got a babysitter and went uptown. About 250 people in all attended.

I hold up a copy of a list of handwritten names Finch photocopied for me. She smiles and says:

I reread that [sign-in] list and the list is so interesting. Two curators from the Whitney came, Henry Geldzahler from the Metropolitan Museum of Art came. There were a huge amount of artists. There were local neighbors. [James] Rosenquist was living on Broome Street with a studio there. Louise Nevelson came! That was great. And then the preservationist [James] Marston Fitch. He was so supportive. And I think one of his students came to one of the public hearings. He was fantastic, he was very supportive because he taught historic preservation at Columbia. He was amazing.

It is a list of formidable heavy hitters, except when you see their names written out in their own handwriting, they become smaller parts of an even more formidable whole. “The art world has spoken,” it says to me.

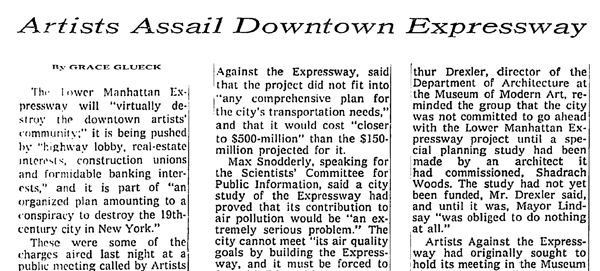

The Whitney meeting was an important turning point in the Expressway fight because Grace Glueck, art critic for The New York Times was in attendance. She wrote an article about the gathering for the arts section that appeared the next day. According to Finch, The New York Times had imposed an informal blackout on reporting on the Expressway until the meeting at the Whitney. Glueck interviewed Finch and broke the blackout. From the article:

The Lower Manhattan Expressway will “virtually destroy the downtown artists’ community;” it is being pushed by “highway lobby, real-estate interests, construction unions and formidable banking interests,” and it is part of “an organized plan amounting to a conspiracy to destroy the 19th-century city in New York.”

These were some of the charges aired last night at a public meeting called by Artists Against the Expressway…

Finch recalls reading the paper on June 20:

We saw the article the next morning, and Rachele Wall [from Community Board 2] phoned me. She said, “Julie, I am so excited. This article in the Times has broken a blackout. They had not printed any articles about our efforts to defeat the Expressway until your museum meeting was written up by the arts reporter. Congratulations!” And she worked in public relations, she was really an incredible organizer and she knew what she was talking about.

Two days later, Artists Against the Expressway met at the 101 Spring Street building, before the Judd family officially moved in, and shortly thereafter, Finch accompanied Wall of Community Board 2 to a meeting with New York State Senator Basil Paterson and members of Village Independent Democrats.

“I was such a purist, such an activist that I was shocked that we were meeting with politicians,” Finch says. She recalls that Wall said to them, “If you drop the Expressway, we will vote for you in the election. She also talked to Lindsay’s people. So that helped a lot.”

Finch and her husband moved into the building at 101 Spring Street in the beginning of July with Flavin, their baby son, in tow, come what may. She recalls the day they arrived in SoHo:

I remember the first meal that Don and I had was a picnic lunch. We went east into Little Italy and we went to a bakery and we bought a loaf of Italian bread. And then we went next door and we bought some salami. And we came back and we sat there on two old bentwood chairs and had our picnic lunch.

Of living at 101 Spring, Finch says, “It was always a work in progress. I was married in ’64, we moved down in ’69, and by the time I got separated in ’76, I still did not have a new kitchen.”

And then, shortly after they moved, on July 17th, the Times reported that Mayor Lindsay, who was running for re-election on the Liberal ticket (though he was then a Republican—it’s complicated, you can read about Lindsay here), declared the Expressway dead “for all time” due to community opposition. This welcome announcement was sudden and surprising to most.

The next day, Borough President Sutton called a press conference in victory, but added he hoped that the Mayor would actually “demap” the Expressway, a planning term that takes a project off the map completely. Demapping would not happen until three years later, but the Expressway plan never reared its head again.

That same day, the influential architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable wrote an article in the Times stating that the cause of the Expressway was now as close to political poison as a candidate can get. She pointed out the inequity in the Lower Manhattan Expressway and other such projects by quoting the rallying cry, “White men’s roads through Black men’s bedrooms.” An alternate solution would have to be found.

“It was amazing that all of the groups, all of the neighborhoods all came together, it was incredible,” Finch says in closing.

Julie Finch is certainly a force to be reckoned with. She’s been a grassroots activist for over 50 years, involved in fights against the Howard Hughes Corporation at the South Street Seaport, Vornado Realty Trust at Penn Station, and as co-chair of Friends of Gibbons UGRR House, to designate an individual building as an Underground Railroad landmark at 339 West 29th Street. Most recently, she gave Zoom testimony against Mayor de Blasio’s SoHo/NoHo/Chinatown Upzoning Plan at a City Council meeting. That meeting brought Finch full circle, back to SoHo, a neighborhood she is fighting for, again.