The following is the seed of a seed of a longer-term project I’m developing that tells the story of artists’ SoHo through oral history.

SoHo was rezoned in 2021, fifty years after it was initially rezoned to allow artist to live and work in their lofts in 1971. Before then, the area that is now known as “SoHo” was a manufacturing district (i.e. non-residential), but as factories began moving out of New York City, artists began moving into vacant lofts that had little in the way of amenities, but lots of space and natural light to make art, to raise a family, to live a life. Artist-activists and the City worked together to make meaningful change.

These excerpts from four oral history interviews with community leaders who were involved in SoHo’s 1971 rezoning shed some light on what it took to shape artists’ SoHo from an urban planning perspective.

Coming to SoHo

Shael Shapiro (Architect):

In the mid sixties, 1966 or so, I started going to a movement therapy group, which was run by a dancer, Joe Schlicter. And Joe was married to Trisha Brown, the dancer …. and at one point he told me, “There’s a loft available in this building.” Someone had bought it, but was afraid it was all illegal. This guy was a doctor and an artist. He was afraid that it wouldn’t work out. So he was trying to sell it. Through that I met George Maciunas, who had organized the building, and I ended up buying that space for the grand sum of $5,000…

I was on a lower floor and there was a very small air shaft in this building adjacent to the next building. Apparently, who knows when, but it could have been 50, 60, 80 years ago, there had been a fire, and this ash shaft had sort of filled up with soot and debris from the fire. It was a window which was broken, and the place was really filthy. We cleaned it up as best we could. We sealed it up, but it was pretty hard to live in the space and work there and fix it and do everything that needed to be done at the same time. So I took some studs and built basically a box covered with plastic and lived in that room until eventually that room became dirtier than the room outside.

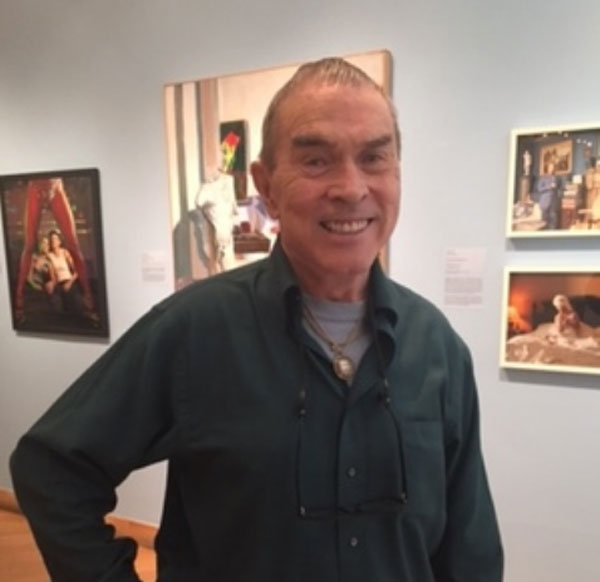

Charles Leslie (Filmmaker and Curator):

[In the late 1960s] I got involved in experimental filmmaking and became very adept at editing and helped some people who were fairly well known in that world. At about the same time I met my life partner, Fritz Loman. …I wanted an editing studio. And I found a tiny ad in the Village Voice saying, “1800 square foot loft in SoHo. Cheap.” Cheap was the salient word for me at that time. So without telling Fritz, I came and looked at it. It was a mess. It was occupied by SDS [Students for a Democratic Society]. Young people don’t even know what SDS was, but they were crazy, I want to tell you. And dealing with them was hair raising.

…I finally bought their place for $3,000, 1800 square feet, which is hard to imagine. It was 131 Prince Street, where I still live. Anyway, of course it was a disaster zone. It was filled with rat poop. It took us two months to clear out the place. It was sort of in such terrible disrepair.

Ingrid Wiegand (Video Artist):

In 1968, Bob and I lived in a rental loft on 4th Street. The area later became NoHo. Bob had just inherited $10,000 when his father died, when he heard that that some lofts were for sale in some buildings downtown. It wasn’t called SoHo then. We looked at one on West Broadway that would have been great, but one of the guys who’d just bought another loft in the building wanted to put his toilet in the living room, and we didn’t really want to deal with that. But the guy we were dealing with was George Maciunas, who was buying other buildings in SoHo. One of these was 16-18 Greene Street, near Canal Street, which he’d just bought for $60,000. He showed us the 5th floor loft that contained nothing but a ceiling-high pile of rubble, from the plaster that George had knocked off the brick walls. The loft had a manual elevator that didn’t work and no water or electricity, but it had 2,000 square feet of open space, with the front full of western light from huge metal casement windows, as well as 3 large windows across the back. We paid George $5,000 for the loft, figuring that the other $5,000 would cover renovations. And by hiring George’s underpaid artist-contractors to do the plumbing and wiring, as well as a lot of sweat equity, we almost did that.

Michael Levine (City Planner):

When I went to work in 1968, the first assignment I had was a few rezonings in the Greenwich Village area to limit the size of new buildings on a street, which was becoming over commercialized at the time, and to be looking at applications we received from residents of manufacturing buildings, it was illegal to live in manufacturing buildings, but we received applications from residents of manufacturing buildings to allow the residential use of manufacturing buildings. We called them lofts. They were all in the SoHo area. The area bounded by Houston street, Canal street, West Broadway and Broadway. We had many, many applications for a way to make their occupancy legal.

They were almost entirely artists who wanted large spaces to live and work in, but they couldn’t legally reside in those floors because residential use was not permitted. As I researched it further, I discovered that they were allowed to live in these loft buildings if they put a sign downstairs on the ground floor called AIR (artist in residence). That meant that two and only two artists were allowed to live in a building above the manufacturing uses. The Department of Buildings, the fire department, and the police department would all know that there were people living on the top floors of these buildings.

What is a loft?

Shael:

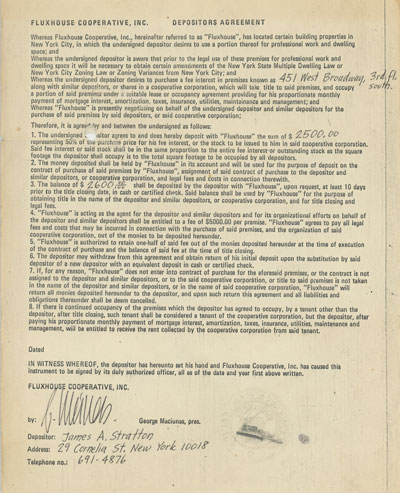

What’s now called SoHo was a manufacturing district under the zoning. Zoning did not permit residential use in manufacturing buildings. At the time, there were plans by Robert Moses to build a 16 lane highway through Broome Street, which would have resulted in demolishing a lot of buildings on half a block on either side of Broome Street. Landlords were anticipating the buildings being condemned and getting money, and they wanted to keep their buildings vacant. But that went on and on, and they had all these vacant buildings. So artists came and said, “Hey, can I have a studio here? I’ll pay you some rent, not very much, but at least you’ll make a little money. Someone will be in your building. It won’t get destroyed.” So artists started to move in, renting here and there in various buildings, and some landlords rented whole buildings, some rented one or two units. It was a very haphazard situation. Then in 1967, George Maciunas, who’s a Lithuanian born architect, graphic designer, artist, started the art movement called Fluxus. He was friends with lots of artists. In the Fluxus movement, the most famous Fluxus artists were Yoko Ono and Nam June Paik. George got together groups of artists and started to buy vacant loft buildings for very little money and organize them as agricultural co-ops because you couldn’t do a housing co-op because you couldn’t have housing.

Ingrid:

The first thing we did was put in a floor because when we first went into the loft, we could see Jim [our neighbor’s] lights through little holes in the floor. We knew that we had to put in a new floor and a new ceiling, so we did that. I got so strong that I could walk around with an eight foot five eighth inch fire code sheetrock, it was like nothing. We actually found that instead of nailing it to the ceiling, there was acoustic track, and we put it up and we bought two guns, and we would go on our individual ladders, lugging up an eight foot piece of sheetrock …and aligned it with the acoustic track and screwed it in. We were able to do about two or three a night.

We finally did the entire ceiling. …And we lay down to admire our work. We started laughing hysterically, both of us, because there was nothing to see. Months and months of work, but there was a ceiling, a white ceiling.

The SoHo Artists Association and the Legalization of Loft Living

Shael:

We all had money invested. For most of us, $5,000. Obviously it was more because I had to spend more money fixing and so on. Let’s say $10,000, it was a lot of money. I didn’t have that kind of money. I was a kid out of college on a first job. We wanted to protect our investments. Even though I always felt that at that point, if I ended up losing it, I was young and I would be able to make it back and survive, which is partly why we did it. I mean, people today who have to buy similar kinds of spaces, it’s a whole other story. At various points there were issues. The city did come around, and sent building inspectors. People used to try to hide. They would hide their beds under a table.

Ingrid:

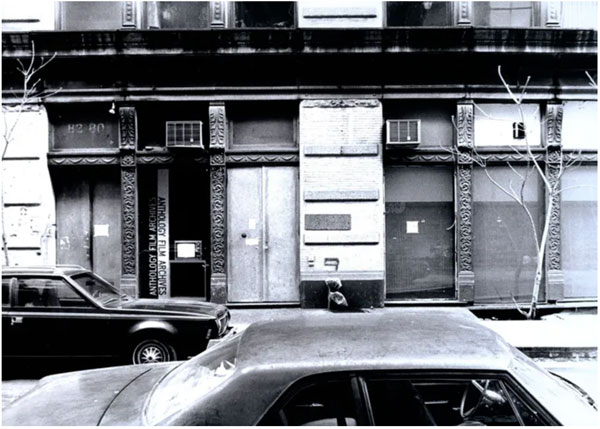

As soon as we bought our loft we found that we were entirely illegitimate and that the buildings that we had spent our fortune on were not legal for living. We weren’t the only ones, there were only a few hundred of us. …The fire department or the police could really make it difficult for you to be there. Whether you were renting or owned it. …Bob and I got together with a bunch of people who were mostly owners like us. A lot of the meetings were at Jeanie Black’s, but also on the first floor at 80 Wooster Street. It was the Anthology Film Archives, and we had a lot of meetings there. That was founded by Jonas Mekas.

…We approached the City Planning Commission, and it’s not the way it is now where you can’t go to the Buildings Department unless you have permission and a lanyard and an ID. We called ourselves the SoHo Artists Association. I don’t think we ever recorded this but we were very much a legitimate organization in the right sense. We were organized. We had a purpose to legalize our lofts that we had bought and in which we were living.

We literally would meet with the City Planning Commission, sitting at a table. We would speak to each other respectfully, but basically the City Plannings Commission members said, “Look, we know what artists are going to do with these lofts. You are going to hang a couple of sheets across and call it a room. This is not in our interest, and God knows how many people you’ll have.”

Charles:

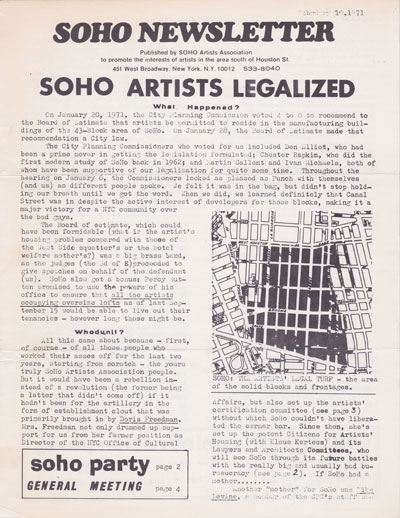

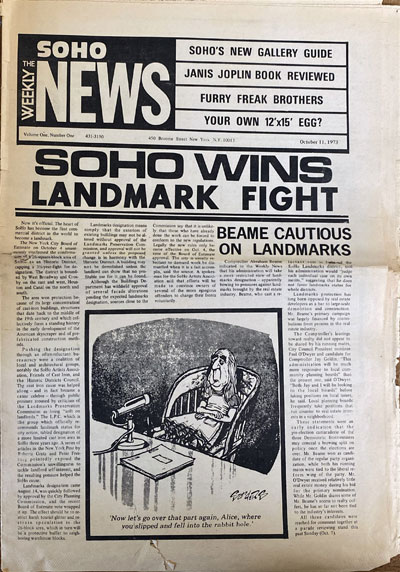

The City Planning Commission had already been approached with the possibility of changing the zoning from manufacturing to mixed use. They said no. Everyone said no in the beginning. But finally, thank goodness we had the last cultivated mayor that we’ve ever had, John Lindsay. We’ve certainly never had a cultured mayor since, genuinely cultured. And he apparently vaguely understood what we were talking about when we were talking about saving the architecture and saving space for artists.

So we finally were able to contact a small organization called Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts. …They dug up statistics, which basically say “What is New York’s number one business?” Everyone thinks it’s finance. It’s not, it’s tourism. Why do people come to New York? They come for theater, for galleries, for museums, for dance, for music. They come for the arts in this town. And here the city is preparing to boot artists out of the nests they have finally found, because there was no place else in Manhattan at that time. There had been thousands of square feet of loft space destroyed downtown, where many artists used to live, to build the World Trade Center. The last resort in Manhattan was this underused kind of afterthought, SoHo, between Canal and Houston and West Broadway and Crosby.

Artists Advocate

Ingrid:

[B]asically, we were middle class in the way we lived. Our places had bedrooms and bathrooms, and they were reasonably clean, our kitchens had dishes and sinks and stoves, our living rooms had couches. They were of different provenances, but we had the accoutrements of middle class life. Our children were really well taken care of and treasured. We were parents. We voted and we were really responsible people. Most of us were really like Bob and I, we put in ceilings and floors and walls, and we didn’t put our toilets in the middle of the room.

Our bedrooms were not walled by sheets. We had a couple of trips where we invited the City Planning Commission to tour our lofts and see not only that we had renovated them in a way that they would approve of, but we actually had learned the building codes. For example, our wires between roofs were not lamp cords, they weren’t just strings. The water was piped through metal pipes and the appropriate quality of metal. Our wires ran through BX cables through the walls, and if it ran on the surface of the walls, it was a metal conduit. We were very proud of that. Our doors were metal, things like that. So we toured them. There were about 10 lofts, and they decided to support us.

Charles:

None of the girls had bras on. There was a little lingering odor of pot in some of the clothes. And I thought, “Oh, we’re dead.” And [Adriana Kleinman from the Department of City Planning] stood in front of us and said, “You must all understand that this neighborhood shall be torn down.” That’s how she began the evening. And we listened to this kind of screed why it was foolish of us to think we could somehow change this neighborhood and use it as living, working quarters. On an impulse, at the end of the meeting, we were all pretty disheartened and I said, “Ms. Kleinman, could I just ask a couple questions of some of the people here before you leave?” She said, “Of course.”

It hit upon me unconsciously. I turned to Jackie Ferarra and I said, “Jackie, when you were matriculating at the University of Salamanca, blah, blah, and Gerhart, when you graduated cum laude from Yale,” and I got into this whole education, there wasn’t the person in that room who had not had been in higher education and mostly in the arts. And she looked at me and said, “And where did you go to school, Mr. Leslie?” I said, “The Sorbonne.” She changed completely. It was amazing. And just before we all said goodnight, someone literally pushed me into her, accidentally. I said, “I’m so sorry.” I said, “Miss Kleiman, I am so ignorant of urbanology and urbanism. Would you possibly be willing to let me talk to you sometime over coffee or something?” She said, “Of course.”

Surveying SoHo

Michael:

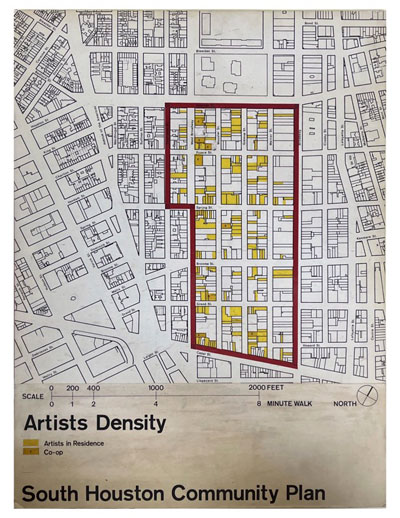

I was then authorized by the supervisors, the director of the Office of Manhattan Planning and the chair of the City Planning Commission to go out into the community, to say that I am a representative of the Department of City Planning, and I’m here to help you make this district legal, but I need to know how many of you there are. That was a bit of a daunting task because so many of them were living behind blackout curtains at night, and did not want to reveal the fact that they were living illegally.

As I went through the district, I made friends with so many of the folk in the area. Ingrid Wiegand, and her late husband, Bob, were very close allies of mine. They had a co-op, and they introduced me to so many of the artists in the neighborhood and helped me to organize research teams to go out into the community and to help me with that census. How many artists are there? Where are they living? That’s who we want to know. Where are you? We don’t want to know your income. We don’t want to know anything else about you, except which buildings you are in. Because if I have a census of who’s here, I can then try to find a way to help you live legally in these buildings. ..

… What I learned was that as I was going down the street, using different survey techniques, looking up at windows to see if they were windows boxes with flowers, looking to see if there were telephone lines hanging from windows, air conditioners, coming back at night to see if I could see lights behind the blackout curtains to help figure out where people were living. They saw me on the streets. What I learned was that they were calling each other and saying, “there’s a young man walking down our streets with a clipboard. He’s our friend, cooperate with him, give him the information he’s seeking. He’s trying to find a way to help us.” That’s what I did for two years, from 1969 to 1971.

Charles:

That spring, Adriana was appointed to do the preliminary survey of SoHo to try and understand how many people were actually living there. She and I spent three months together every evening going from door to door. And at that time, people who lived in front lofts literally had virtually blackout curtains in front of their windows because they didn’t want to be detected.

That summer we’d knock on doors, and I already knew several people in the neighborhood, so they weren’t nervous when they saw me. But then when I stepped in with this pert little woman in a pleated skirt in a silk blouse, they wondered where she was coming from. I always had to lead with “This is Adrianna Kleinman who’s trying to help us get legalized.”

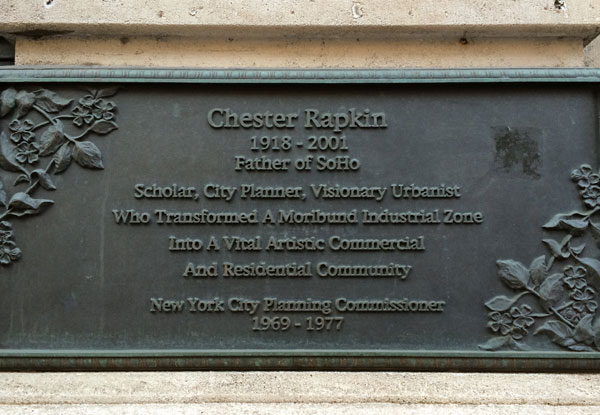

We found 700 people in residence that summer. All illegal. I knew there were lots, because we’d met so many people, but 700? I had no idea. She reported back and then the really serious, academic, very formal study began under the direction of Chester Rapkin.

A Zoning Change

Michael:

The city is divided into a series of districts called zoning districts, and the basic configuration is residential, meaning residential only, commercial, which includes storefronts. It includes office buildings, and it includes a limited number of residential uses, and manufacturing. So the three basic districts are residential, commercial and manufacturing.

Ingrid:

In 1969, I don’t remember the details, but the state changed the Multiple Dwelling Law and the city designated parts of SoHo. SoHo was what the city considers a manufacturing district, M1-5… They divided SoHo into M1-5 B and M1-5 A.

Shael Shapiro, who was an architect and lived down here, he was very much an artist-architect. He dealt with the New York City buildings department to work out the building requirements for the change of these special districts. He really worked hard and really his contribution was great.

Shael:

The zoning was changed in 1971. I think the moment was right. Probably a year or two later, or a year or two earlier, it wouldn’t have happened. But John Lindsay was the mayor and he was a big supporter of the arts and the head of the Department of Cultural Affairs was Doris Freedman, who came from a wealthy real estate family who was very supportive of the arts, who thought that this was the greatest thing that artists could do. And it was that pretty much everyone thought was a good idea except for the commercial real estate interest.

City Planning had commissioned another report by a planner named Chester Rapkin, and he wrote a report showing that there were a lot of jobs in buildings. You didn’t really see them, but there was a huge number of semi-skilled and skilled manufacturing jobs still in those buildings, and that the city needs to protect those jobs. And City Planning was amenable…the idea being that artists could live and work in some of the lofts. … It didn’t make sense for many kinds of companies…to be in these buildings anymore. The streets were narrow or there were no loading docks. Elevator access was limited, but the city wanted to keep the jobs. So they came up with this compromise of artists could live in the lofts.

Cast Iron Architecture and Preservation

Charles:

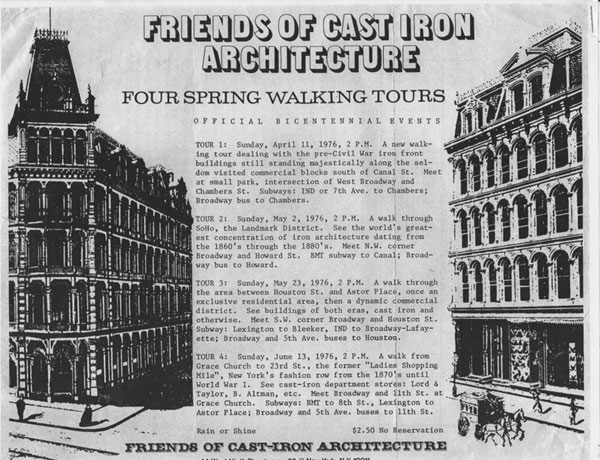

I learned of the existence of Friends of Cast Iron Architecture, led by a wonderful Southern Belle named Margot [Gayle]. She was devoted to cast iron architecture. And so we started doing a study of cast iron architecture that got us involved with the Landmarks Preservation Commission. We finally were able to have them help us show that iron architecture was the first solely American contribution to architecture in the world. And before that, everything we did in America was a copy of something done in Europe. But, cast iron architecture was a purely American invention. … SoHo still has the most important conglomeration of cast iron buildings, and they were in pretty bad condition. So then once Landmarks got involved, then you had to start really taking care of them, which was certainly a burden on the people who had bought into the buildings, because it was an expensive process to restore metal work. Now SoHo looks pretty nifty, I think.

Michael:

And I said, “I don’t think there are very many people in the city of New York who are aware of the fact that we have such a treasure trove of buildings built in the late 1800s from cast iron, using these wonderful columns.” As the buildings go up to the sixth floor, the top floors get shorter to follow the architectural pattern, making it look like a taller building. You look up and if it’s a shorter floor, you say, “OK, it’s a very tall building.” I began to appreciate all the architectural touches that these buildings had and I photographed it all. On the one hand, I saw extraordinary gritty, manufacturing. I saw broken sidewalks, cracked cobblestones, a lot of garbage, a lot of unsanitary conditions, but absolutely beautiful, exquisite buildings.

The Future of SoHo

Charles:

[Chester Rapkin] sat in my loft and warned us. He said, “Now, you know, if we succeed and get the zoning change, you must understand that this neighborhood is not going to remain an artist neighborhood forever.” And we said, “Oh, poo poo, of course it will.”

He said, “No, you don’t understand. Once you’ve done that, you will have a tiger by the tail. Cities have a way of doing what they want to do, not what you want them to do.” Undaunted, we plowed ahead.

They always say, If you want to gentrify a neighborhood, you do one of two things, or both things at once. You have a lot of artists move in, or you have a lot of gay people move in, and suddenly things will start to percolate. We had both.

I thought it would solve the problem. And of course, we were warned by Chester Rapkin. He said, “No matter what legal steps are taken, this neighborhood will become whatever it will become. And you cannot count on it not happening.” And he was right, because people wanted to live here, hedge fund managers, Wall Street brokers. I knew it was over one morning when I was walking down Wooster Street, and there was this chic little Roadster convertible sitting out front. And a young man and a young woman came out with tennis togs and an Afghan dog. I thought, “Well, there goes the neighborhood.”

Chester Rapkin told us, “Once the realities of urban finance take over, you have no control anymore.” And he was right. We said, “Oh, no, no. We’ll control this.” You can’t control it.

Shael Shapiro was interviewed by Roslyn Bernstein in October 2015 at Foley Square, NYC for the The SoHo Memory Project / StoryCorps day of recording.

Charles Leslie was interviewed by Susan Wittenberg in December 2014 at the Leslie-Lohman Museum, NYC for SoHo Stories, a SoHo Memory Project / New York Public Library Neighborhood Oral History Project.

Ingrid Wiegand was interviewed by Yukie Ohta in 2023 at her home in NYC for SoHo Memory Project.

Michael Levine was interviewed by Yukie Ohta in 2022 via zoom for SoHo Memory Project.

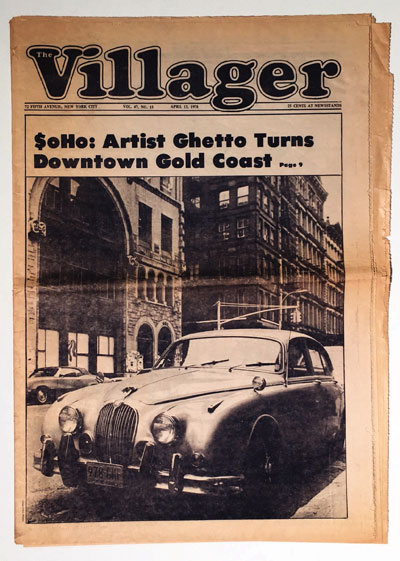

(top image: SoHo Artists Association meeting, 1970. Photo: John Dominis via Archives of American Art)