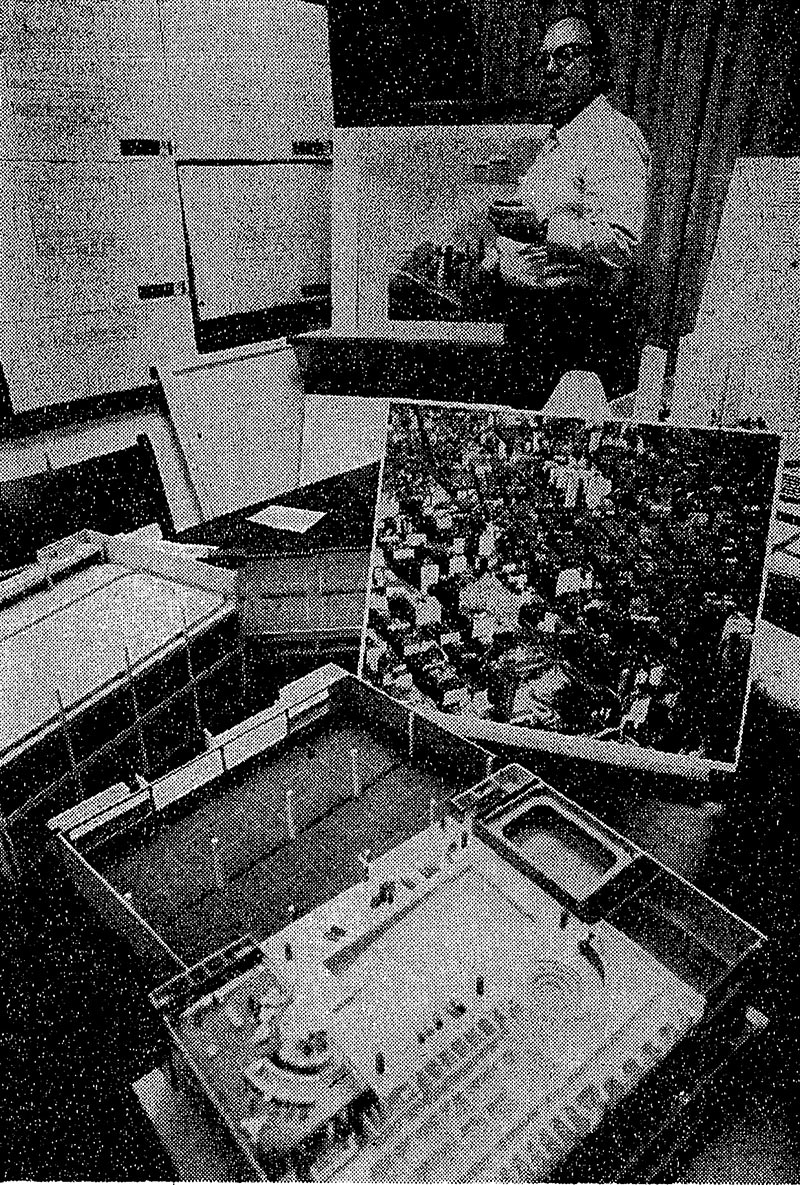

Charles L. Low with drawings and models of his proposed sports complex (photo: The New York Times)

Did you know that the second biggest development project never to happen in old SoHo, after LOMEX, was a proposed sports complex? In 1972, the real estate developer Charles L. Low asked the City for a variance to build a 21-story public sports center at 311 West Broadway, just north of Canal Street. The complex was to have 15 tennis courts, four ice skating rinks, a 6,000 square foot gym with running track, six squash courts, two handball courts, a 25-meter Olympic swimming pool, a whirlpool, sauna and exercise rooms, lockers and dressing rooms, lounges, health food bars, pro shops, a nursery, and self-service parking for 225 cars. The complex was to mainly cater to the Wall Street crowd and other white-collar types who worked downtown. In 1972? In SoHo?

Needless to say, this plan caused some controversy. And, as you can guess, the complex was never built. But for a while, when the plan was still a possibility, it caused a huge divide in the SoHo community and its environs.

Many but not all artists who lived in SoHo were against the plan. The most vocal opponent was the SoHo Artists’ Association, who argued that the complex would spoil the character of the neighborhood, that it would be an eyesore in a neighborhood that was made up of low-rise, 18th century buildings. They also argued that the complex would bring in more people and automobiles to the neighborhood than it could support and it would also lead to higher rents in an area whose rents had already doubled in recent years due to escalating property values.

On the opposing side, community members, most of whom lived just west of West Broadway, most of whom were Italian-American, and most of whom were not artists but laborers and merchants, supported the plan, arguing that the complex would raise the profile of the neighborhood, bring much needed jobs to the area, and would provide a place for residents, especially children, to exercise (the students in the nearby Catholic school were promised free access to the facilities). In addition, NYU supported the plan, as the complex would improve the quality of life of their faculty members who lived nearby.

Both sides had compelling arguments. It was a bit of a surprise, though, when the complex was defeated. As Donald Tricarico explains in his book, The Italians of Greenwich Village: The Social Structure and Transformation of an Ethnic Community:

The SAA was persuasive. The planning board adopted its position and advised against the complex. Italians were quite angry and taken off guard by the artists’ assertiveness in the matter. The community broker felt that the sports center was “none of their business.” He also felt betrayed. He insisted that “if it wasn’t for the Italians, there wouldn’t be a SoHo.” (p. 130)

In hindsight, I suppose I am happy that the complex was never built. One less aesthetically questionable behemoth building to look at. Yet, all of the things that the SAA said would happen to the neighborhood if the complex was built happened anyway. And pretty soon thereafter. On the very same plot where the complex was supposed to be, we now have the SoHo Mews, a sprawling luxury condo complex where the likes of Oscar de la Renta own property, and across the street is the majestic SoHo Grand Hotel. And neither the Mews nor the Grand serve the youth of the neighborhood (though I don’t 100% believe that the sports complex would have in the end, either—lesson learned from the whole Coles experience). To the west of the Grand, we have the even more majestic Trump SoHo Hotel. If the names “Trump” and “SoHo” can be found proudly emblazoned on a marquis, I think we can safely say that we have crossed the Rubicon.