The following is an excerpt from Chapter 2 of SoHo: Beyond Boutiques and Cast Iron-The Significance, Legacy, and Preservation of the Pioneering Artist Community’s Cultural Heritage by Susie Ranney, who recently completed her M.S. in Historic Preservation at Columbia University. Ranney consulted with me while doing research for her project, which uses “a critical study of the span of preservation intervention in the SoHo district of Manhattan to inspire the responsible stewardship of the early artist community’s cultural heritage in the public memory and the physical environment of SoHo.” The thesis contains a wealth of background information about everyday life in SoHo, including this excerpt about elevator, doorbell, and dumpster etiquette (some of which has been covered in past posts but merits a revisit), as well as etiquette when interacting with SoHo’s weekday population, the factory and warehouse workers.

Note: The photographs that appear in this excerpt do not appear in the original text. They were added for the purposes of this post.

Heritage: Collective Identity Rooted in Art and Landscape

by Susie Ranney

Beyond the buildings that define the landscape and the visual expressions of this landscape into art, the first generation of SoHo artists established an inherently “SoHo” sense of place through the creation of closely aligned community culture.(38) Regardless of age, gender, sexuality, or race, the residents of early artists’ SoHo coalesced into a stable and supportive community of friends, colleagues, mentors, and patrons. The “illegal” auspices of their residency and a shared passion for art apart from the mainstream facilitated connection. Furthermore, as the decade progressed and the artists took an increasingly greater role in securing the neighborhood’s survival, the shared experience of fighting for their homes brought the residents closer together. But the most important component in the coalescence of SoHo as a community was the set of unspoken and unofficial rituals of living amongst the artists. Enabled and shaped by the SoHo environment, the rituals were defined by display and performance, the creating and sharing of food, and a sense of humor of their circumstances. The rituals of Artists’ SoHo were sometimes scheduled and often improvised but were integral to the collective identity of the community.

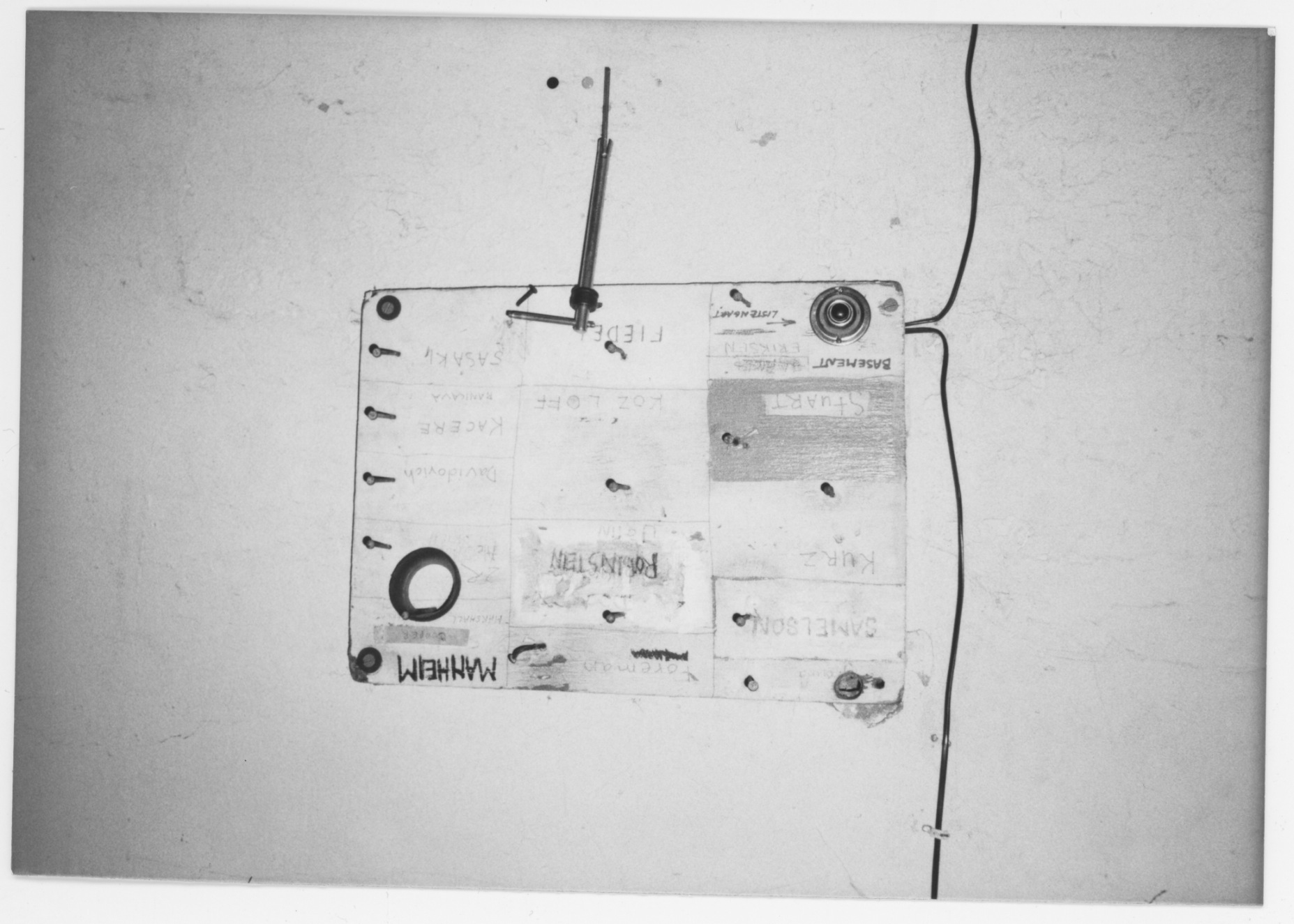

The use of a freight elevator involved a complicated etiquette (photo: Yukie Ohta)

The community residents developed certain rituals and codes of conduct in order to adapt to residential living in the midst of an industrial landscape. For example, while some of the buildings did have passenger elevators, a great many buildings had only rickety stairs and a single freight elevator to provide vertical egress and be shared by all tenants. Particularly for residents on the top floors, the freight elevators choreographed much of the movement throughout the buildings. During the weekday business hours, the companies would provide an elevator man, as the elevators nearly always required manual operation from within the car. The elevators in these buildings were almost always of the first generation of industrial elevators, and though the lifts, like the cast iron buildings, had been groundbreaking technology, nearly three-quarters of a century later they were archaic, slow, temperamental, and aggressive-looking. One of the first major expenses of the co-op (and, later, the developer) in converting a loft building to residential use was to install an automatic elevator that could be called to a floor without being inside the cab. Such a luxury was rare in first-generation SoHo, however. For usage after-hours and on the weekends, the residents developed codes of etiquette for elevator operation.(39)

In cooperative buildings, a resident was typically appointed as the elevator’s keeper, making sure that the elevator was recalled from the ground floor at the end of the night. Out of courtesy for this individual, it was understood that if one returned home past a certain time, one simply took the stairs. And if the elevator was unable to be accessed, residents simply had to get creative in admitting visitors:

As industrial buildings didn’t have doorbells, an upstairs artist often installed a bell near the front door and ran a wire directly into his loft. However, since the resident lacked an electrical connection to open the floor door, he or she had to run downstairs to open the building’s front door or, more conveniently, throw a key customarily inserted in a thick sock.(40)

Other alternatives included yelling up to the resident or calling from a nearby payphone. When the elevator was simply at another floor, rules of etiquette again applied:

For after-hours, the residents necessarily agreed that whoever last used the elevator to get to his or her floor would be responsible for answering the next bell, taking the elevator to whichever floor demanded it. [Whoever had summoned the elevator would then take the other resident back to their floor].(41)

All the while, visitors would be forced to stand outside on a deserted sidewalk in a seemingly abandoned, non-residential neighborhood in varying degrees of darkness in the midst of Manhattan.

A typical SoHo doorbell system (photo: Jaime Davidovich)

To a degree unknown in residential neighborhoods, the streets of SoHo were filled to bursting with workers and commercial trucks during the working hours of week and deserted at night because residential occupation was illegal. Although various city organizations, from the Real Estate Board to the non-affiliated City Club, produced reports such as “The Wastelands” that proliferated the notion that industry in SoHo had largely disappeared, Rapkin’s 1963 report documented the continued presence of a variety of businesses and a substantial workforce, claims supported by testimony from tenants and businesses of the district. For the artist and non-artist residents alike, the street scenes provided daily entertainment, inspiration, and annoyance.

Workers at a candy factory (photo: Shael Shapiro)

Regardless of one’s feelings, the daily patterns of business activities were an important component of living in the district. Workers and residents interacted in the freight elevators and bartered for goods from each other.(42) During breaks, workers populated the streets and “would gamble on the sidewalk, tossing coins against the wall, while they drank cans of beer.”(43) Seemingly unperturbed by the presence of secondary group of laborers, the workers accepted the uncompetitive presence of the artists, and, like the district itself, despite rather rough or even menacing appearances, the workers (and district) were generally benign:(44)

The neighborhood was deserted. Early one morning, when [80 Wooster Street resident Jeanie] Black left for school in her car, a 300-lb guy came running after her…. “It turned out that he only wanted to tell me that I had left my school books on top of the car.” Black soon learned that although the neighborhood felt empty, it was safe.(45)

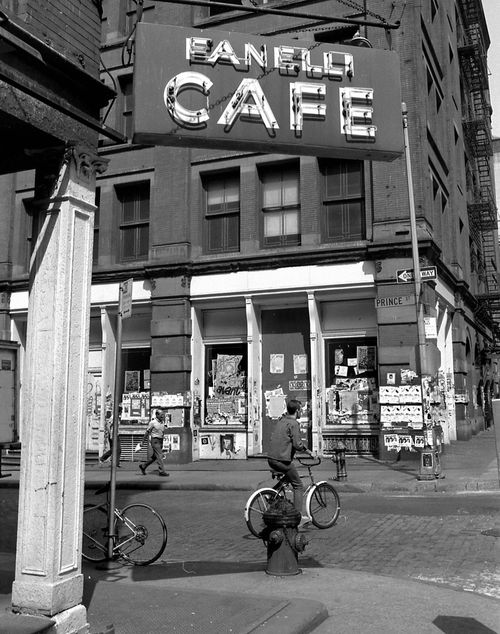

Until the arrival of the artists, the workers were the sole patrons of the area’s only restaurants, the hours of which ran according to business schedules. Two favorite worker-originated restaurants were critical to the SoHo social scene and feeding of both parties: Kast’s Luncheonette and Fanelli’s bar.(46) Ultimately, communal accord was struck between the two stakeholder groups of SoHo in the eating and drinking establishments. As neutral territory for both the workers and artists, Fanelli’s played an important role in the integration of the workers and artist-residents through its shift from rough-and-tumble workers’ haven to community hangout.

Fanelli’s (photo by Dave Glass/Flickr via Alex/Flaming Pablum)

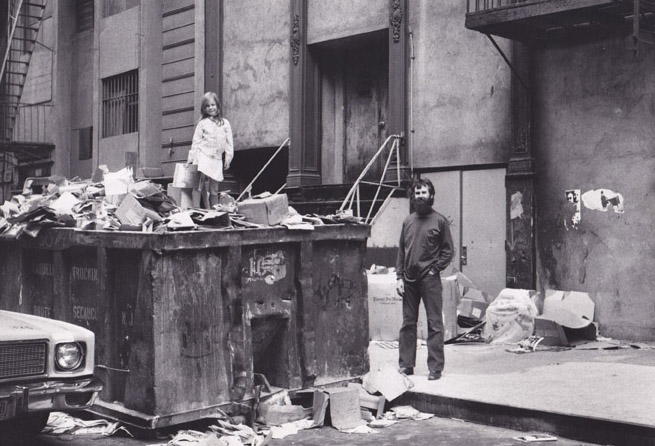

Apart from the bars and luncheonettes, the existing businesses of SoHo provided the artist community with rich sources of material for artistic and home décor purposes. In the recollections of nearly every SoHo residents, reference is made to street-salvage activities as standard parts of daily life. Even into the 1970s and the waning days of the industries, the streets of SoHo “were filled with piles of industrial stuff: wood, metal, rubber, textiles, construction material, and whatever.”(48) Salvage was common as late as 1974, when Richard Kostelanetz, who had long visited artist friends in the district, moved to a George Maciunas-run cooperative building:

Picking not only furniture but art materials off the street was a neighborhood game. Once I moved to SoHo, I found many of my bookcases on Friday evenings, which has been the designated time for putting out larger trash in my neighborhoods. Almost every evening I could find skids to keep certain furniture off the floors….(49)

Dumpster diving provided a round-the-clock counterpart to street salvage, and, akin to freight elevator operation, rules and etiquette established procedure for the event. Kostelanetz explains, “The first rule was not to approach any trash containers while someone else was selecting objects. It was also de rigueur to put the trash back into the containers when one had finished making choices.”(50)

A dumpster on Mercer Street, ca. 1977

Gordon Matta-Clark even went so far as to encourage such behavior when, “[He] put on the street [in front of 112 Greene Street] an industrial dumpster into which artists were invited to put things as well as [to] take [from the selection].”(51) The harvesting of urban detritus for artistic use facilitated the art ists’ pursuit of producing art and redefining urban life in a decidedly non-traditional, non-serious, and non-formal manner.(52) Furthermore, repurposing discarded manufacturing paraphernalia into pieces that were both works of art as well as useful household objects allowed the artists to reinterpret the physical character of the SoHo district into their domestic and professional art.(53)

….

The unique result of the temporal and physical context and the individual participants, the collective identity of the Artists’ SoHo was expressed through the lifestyle, art and activities in which the residents participated. The artist community appropriated the raw material of a historic, fading, but still active manufacturing landscape and through response and manipulation developed a distinctive identity and heritage. The mutual adaptability of the physical environment and the artist residents, the equilibrium achieved between the artists and the industries, and the residents’ desire to investigate various talents generated the cultural “Artists’ SoHo” and enabled the community to create a largely self-sustaining system of living.

Note: The remainder of this chapter discusses in depth the restaurant Food and the exhibition space 112 Greene Street.

Notes:

38 Richard Kostelanetz describes the district at this time as a “college campus,” a statement that rings especially true when considered as a slightly physically separated, cultural institution for learning, discovering one’s self, and participating in experiments of social and civic expression. (Kostelanetz, SoHo: The Rise and Fall of an Artists’ Colony, 36.)

39 Ibid, 24. SoHo: Beyond Boutiques and Cast Iron 39

40 Kostelanetz, SoHo: The Rise and Fall of an Artists’ Colony, 23.

41 Ibid.

42 Kostelanetz, SoHo: The Rise and Fall of an Artists’ Colony, 23.

43 Bernstein and Shapiro, Illegal Living, 122.

44 Kostelanetz, SoHo: The Rise and Fall of an Artists’ Colony, 25.

45 Bernstein, Shapiro, and Mekas, Illegal Living, 122.

46 Kast’s Luncheonette is now Boom Restaurant, on Spring Street. Kast’s closed following lunch service and on weekends. (Bernstein and Shapiro, Illegal Living, 122.)

Fanelli’s Bar is still open at the Southwest corner of Prince and Mercer Street. Taken over by Mike Fanelli in 1922 but open since 1847, Fanelli’s is the second oldest continuously public establishment serving food and drink in New York City. A piece of true New York City history, the current owners promised Fanelli upon taking over the business that they would not alter the restaurant interior. A soup post has been added to the exterior but is located in a previously existing shed.

(Yukie Ohta, “The Café on the Corner,” The SoHo Memory Project, Accessed 6 Mar. 2012.

47 The major shift occurred thanks to the enterprising local artist collective Videofreex, who aired a recording of the entire 1971 Muhammad Ali-Joe Frazier at Fanelli’s. Apparently, the bar was standing room only for the rest of the afternoon and night, and a group (employees or customers, it is unclear) had to make emergency beer runs. (Kostelanetz, SoHo: The Rise and Fall of an Artists’ Colony, 25.)

48 Artists looked out for each other and left signs such as “it works,” on discarded equipment so that their peers would seize the opportunity before the trashmen took away the spoils. (Kostelanetz, SoHo: The Rise and Fall of an Artists’ Colony, 24.)

49 Ibid, 25.

50 Id.