If you live anywhere in lower Manhattan, no doubt you have heard about the Envision SoHo/NoHo planning process sponsored by the New York City Department of City Planning (DCP), Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, and Councilmember Margaret Chin. According to its website, the Process Sponsors intend “to examine key land use and zoning issues in the two neighborhoods and seek community input to develop strategies to both honor SoHo/NoHo’s history and ensure the continued vitality of the neighborhoods.” SoHo is historically an artists’ neighborhood, so one would assume “community input” would include artists, but this is currently not the case, at least officially. There is not a single artist in the Process Advisory Group that will “help develop recommendations to inform the future of SoHo and NoHo.” If the Project Sponsors truly seek community input, artists must be included in all phases of the process.

A team from BFJ Planning, a consulting firm, has been tasked with presenting a list of recommendations for achieving Envision SoHo/NoHo’s stated goals on June 6. To this end, they have held a series of public workshops “on topics including housing, jobs, arts and culture, preservation, retail, quality of life, and creative industries.” At a February 28 workshop entitled “Defining Mixed Use,” a City Planning staff member presented current economic data to workshop attendees in which artists were not included as part of the workforce in SoHo. With a show of hands, about 85% of the over 200 attendees were artists, and they certainly felt disenfranchised by being omitted from the picture all together. It quickly became clear that the Project Sponsors need a clearer sense of how many artists are living and working in SoHo, certified and non-certified, before any planning moves forward.

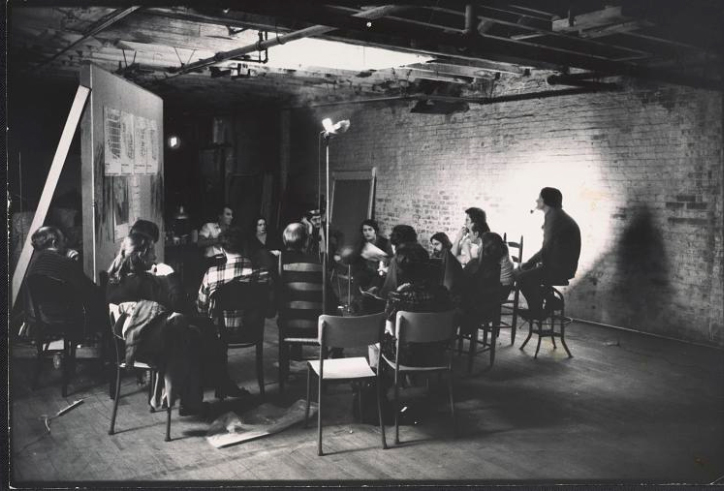

Ingrid Wiegand, founding member of the SoHo Artists Association (SAA), that later evolved into the SoHo Alliance, and Michael Levine, the urban planner who helped craft the 1971 law to allow SoHo artists to live in former industrial buildings, spoke at the meeting. They described how, over a period of two years, they counted artists block by block back in the late 1960s to determine who the stakeholders in the neighborhood were. (See the 1970 SoHo Survey report here.) This type of census may be impractical, if not impossible, to conduct today due to high population density. However, something perhaps short of a headcount, but something much more than mere speculation about the artist population in SoHo and NoHo is in order.

Artists have made themselves heard through vocal community engagement, yet the issue remains that artists are not represented in any official capacity. “This is really the beginning of the process,” Jonathan Martin of BFJ told the participants at the May 2 Envision SoHo/NoHo public workshop. According to the Project Sponsors, the June 6 report is intended to be the first phase in a longer study period to determine if modifications to existing zoning or a re-zoning is necessary to achieve the group’s goals “to both honor SoHo/NoHo’s history and ensure the continued vitality of the neighborhoods.” If this is the case, artists must be included in the next phase and moving forward if the process is to be legitimate.

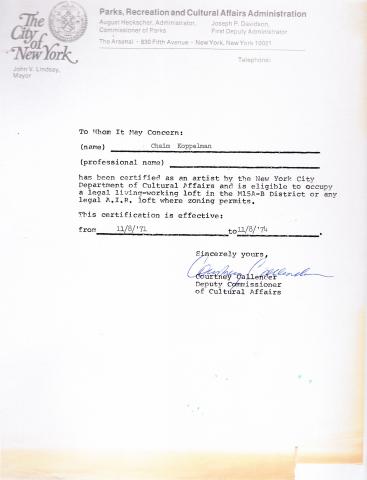

Several long-time SoHo residents I spoke with about the prospect of zoning revisions were members of the SAA, who partnered with DCP in 1971 to enact current zoning policies, the very policies that started the ball rolling by creating JLWQA (Joint Living-Work Quarters for Artists) and got us to where we are today, an M-1 (light industrial) zone that allows for artists, who manufacture art, to live in their work spaces. They have the long view of the evolution of SoHo as a mixed-use community and feel that they should have a place at the table in this go around as well.

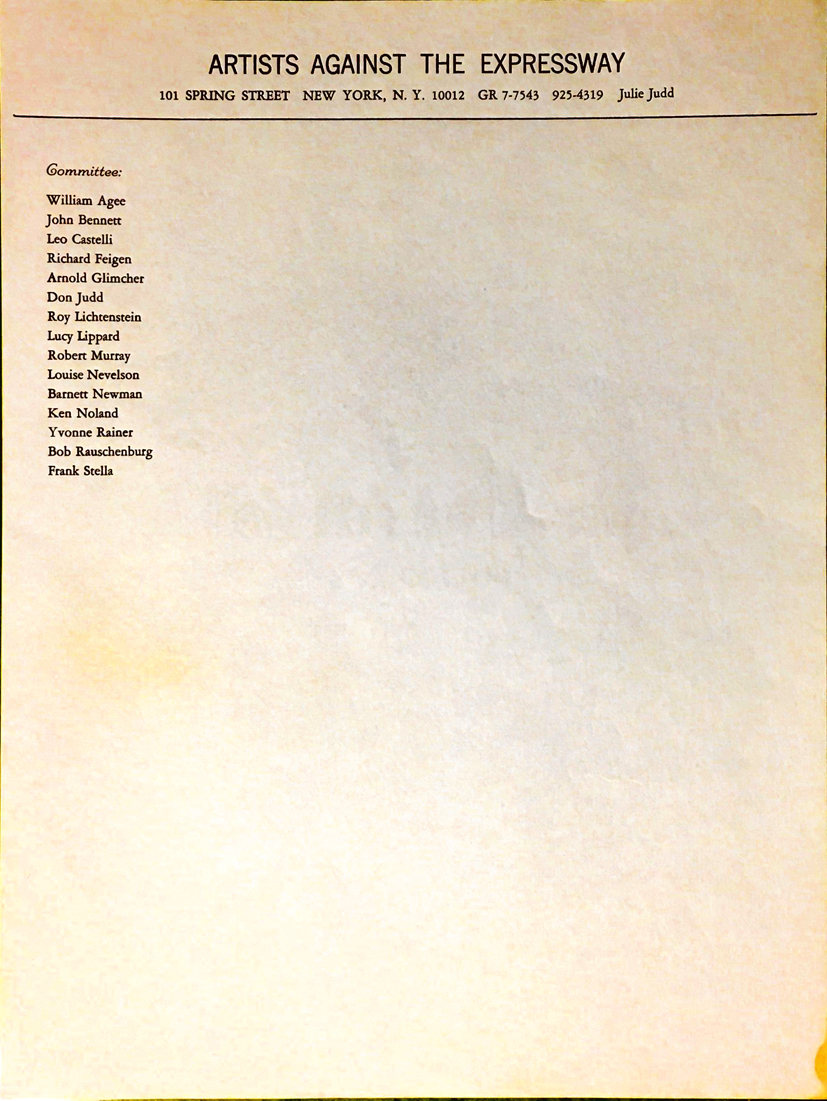

“Without artists there would be no SoHo,” says Julie Finch, artist and founder of Artists Against the Expressway, the group that helped defeat Robert Moses’ proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMEX). Slated to be built across the length of Broome Street, it would have obliterated the neighborhoods surrounding it. If the expressway had been built, there would be no SoHo today. “Artists Against the Expressway is an example of how artists can make a difference,” she adds. Finch and her husband, artist Donald Judd, mobilized their allies in the art world to oppose and eventually defeat the LOMEX plan in 1969.

Artists who moved to SoHo as early as the 1960s feel that it is crucial for DCP to protect the artists for whom JLWQA was created. A 1969 statement by the SoHo Artists Association in support of zoning changes to protect artists points out that artists “have established New York’s status as the cultural center of the United States, a position which in its turn attracts the industrial and commercial giants that make the City live.” Fifty years later, this statement still holds true. Companies, as well as tourists, come to SoHo because of its reputation as a creative capital. Without this cachet, SoHo loses much of its unique character and allure.

Many SoHo artists suspect that groups with commercial interests in the area continue to put forward the false notion that there are no longer artists living in SoHo, that they do not need to be considered or protected because they do not exist.

“I think there are a decent number of artists in SoHo,” says Shael Shapiro, an architect who had a hand in converting many of the area’s industrial buildings into artist co-ops in the late-1960s and early-1970s and also helped adapt article 7B of the multiple dwelling law that legalized artist lofts in 1971. “It’s not a handful, what some people seem to think, but is it 30, 40, 50 percent? It’s hard to know.”

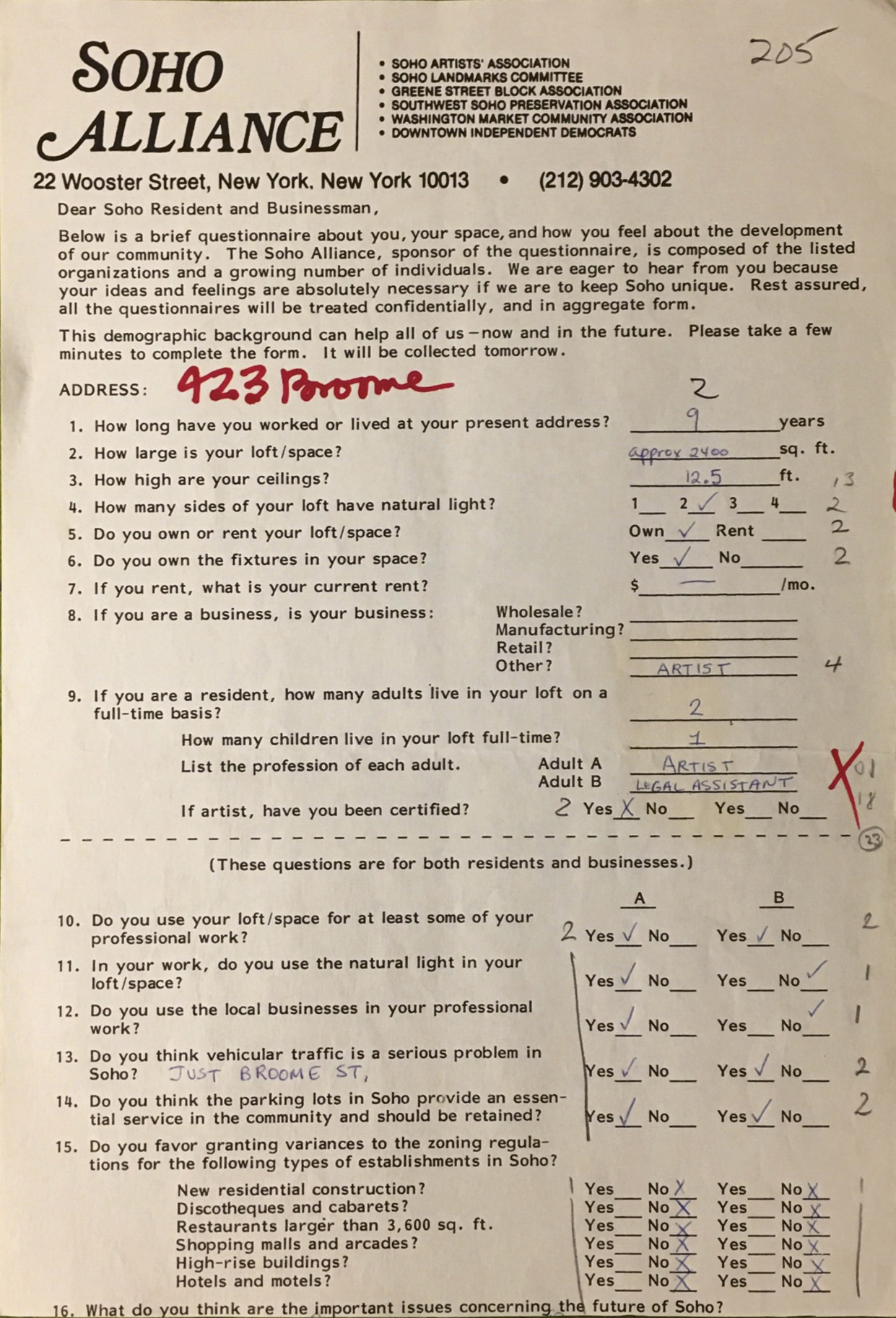

This longstanding notion is cited as far back as 1983, when the SoHo Alliance conducted a second SoHo Survey (See the 1983 SoHo Survey report here):

There are no more artists in SoHo: only doctors and stockbrokers. It’s so expensive in SoHo that no artist can afford it. There is no more manufacturing left in SoHo–there is no industry there to protect.

The SoHo Alliance has heard all of these generalizations about SoHo and has long been irritated by them. While the Alliance survey of SoHo was not originally intended to debunk any of these preconceived notions, the results strongly confirmed what we had felt to be the case from our knowledge of the area. It indicated that a great many artists remain in SoHo, that they have lived there for quite some time, and that their rents are NOT the astronomical figures often quoted in newspaper ads.

If another such survey were conducted today, it would likely show that there are, in fact, many artists still living and working in SoHo, albeit fewer than in 1983. Since then, many non-artists have replaced artists, as JLWQA regulations have not been enforced for many years. Among the long-time SoHo resident-artists I’ve spoken to recently, many are sympathetic to these “new illegals,” non-artists living in SoHo, because they themselves were once living in SoHo illegally. They would like to see the rights of all residents, legal and illegal alike, protected.

In short, word on the street, at least on my street, is that the needs of all stakeholders must be equally considered and protected. “We need to balance the equities,” Shapiro says, referring to a series of publications put out by DCP in the early 1980s entitled Lofts: Balancing the Equities that sought to “balance the legitimate but conflicting needs of industrial and residential uses for loft space. Back in 1971, [when DCP made loft living for artists legal in SoHo], we tried to create a balance between all the various needs. There needs to be a new balance of the equities now.”

For more on SoHo zoning, including the difference between JLWQA and AIR, see my article in Urban Omnibus: Living Lofts: The Evolution of the Cast Iron District.