Recently, I came across three short films about SoHo, Ingrid Wiegand’s “Walking,” Ming Mur-Ray’s “Surviving SoHo,” and Paul Tschinkel’s “SoHo Stories – Colette and Cindy Sherman.” Each illustrates in its own way what it was about artists’ SoHo that allowed it to flourish, albeit briefly, before gentrification crept in—a happy coincidence that presents an interesting glimpse into the everyday lives of four artists that shows us a little bit about what made artists’ SoHo tick.

Walking (interstices) A 1975 experimental video by Ingrid Wiegand documenting common events in one of the artist’s days. From the Robert Wiegand papers and video art collection, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. (15:38)

The earliest of the three films is Ingrid Wiegand’s 1974 experimental video “Walking,” a film about making a film about the artist’s everyday life. Of the film, Wiegand says her days “were the raw material, but it was really about my making it.” The video shows us, among other things, how family life and working life melded together in the everyday lives of her family. Wiegand’s video art bluntly documents the quotidian, in which there is no boundary between her work and her non-work lives, they are one and the same.

“Walking” is framed by shots of video equipment and cables in Wiegand’s workspace, but what we see in between are a trip to the SoHo playgroup, to the Grand Union (now Morton Williams) and to her husband, artist Robert Wiegand’s studio where he is working on a large piece to be exhibited later that year, along with “Walking” which is then still in the making. These scenes are intercut with footage of Weigand working on “Walking,” her voice narrating her thought process.

Footage of Wiegand’s daughter, Indira, and other local children remind us that Wiegand is doing double duty as she films, she is making art and parenting. When she asks Indira what she wants for breakfast, Indira replies, “Camera!” (Note to SoHo Playgroup alums: In addition to Indira, we see Ilsa, Dov, Vanessa, and a few others here).

Surviving SoHo An intimate portrait of Rosemarie Castoro, a prolific artist and sculptor. The camera follows her from the streets of SoHo, NYC to her art studio. Director, camera, editor, Ming Mur-Ray 2004 (12:15)

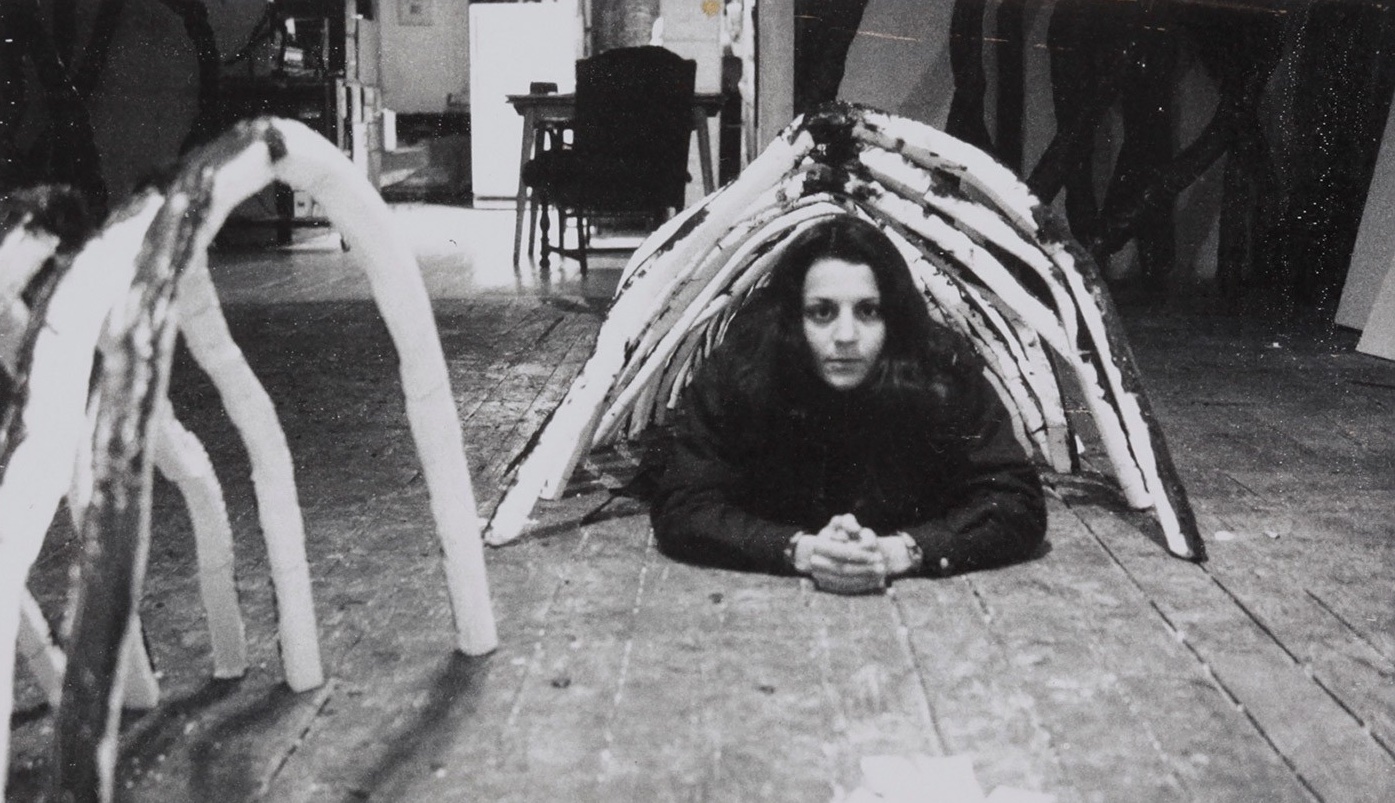

This seamlessness is also seen in Ming Mur-Ray’s “Surviving SoHo,” a 2004 short film about sculptor Rosemarie Castoro, pictured above in her live-work studio (“Pet Tunnel” installation view. (Photo: Courtesy of The Estate of Rosemarie Castoro, copyright: ERC Holdings, LLC 2022)

The film opens with Castoro’s voice saying, “The neighborhood, Hell’s Hundred Acres (what SoHo used to be called before it was SoHo), was very dark, dangerous, and one did not walk at all on Mercer Street.” The camera follows Castoro walking through the streets of 2004 SoHo, and moving through her live-work studio, surrounded by many of her stainless steel sculptures. She keeps a large work entitled “Tunnel,” that will be purchased by MOMA’s Agnes Gund on her roof. “They’re horrified that I put it on the roof, but we have to find places for our works, and sometimes these places are in dangerous spaces,” she says. Wet basements, barns with termites, rooftops that are open to the elements.

In a later scene, Castoro’s dentist, in whose office some of Castoro’s smaller works are displayed, explains that during a procedure, she will ask for a pad and pen when “she gets moments of inspiration and all of a sudden she’ll g ‘aha!’ ….and before you know it she has the idea for a totally different direction for her artwork.”

The most interesting shots are of Castoro welding, creating her steel sculptures in her live-work space, where she explains that before loft living was legalized, her kitchen was set up as an office and she kept her pots and pans in file cabinets and lockers, presumably in case a building inspector showed up unannounced.

SoHo Stories – Colette & Cindy Sherman Colette the Artist and Cindy Sherman have experienced the flourishing of SOHO in the 70’s and early 80’s and here they describe some of the exciting times of living and making art in this then dilapidated, abandoned neighborhood. Film by Paul Tschinkel. (5:30)

In the third film, Paul Tschinkel’s “SoHo Stories – Colette and Cindy Sherman” (comprised of interview excerpts from a longer film in progress), Colette describes artists’ SoHo as mysterious, dirty, dark, poor, and dangerous, echoing Rosemarie Castoro’s words. “All the ingredients for great art,” she says, which speaks to the notion that artists’ thrive in a community of like-minded, single-minded folk who have not shown up for material comforts, but to do one thing and one thing only: make art.

Colette started out in New York painting the streets of the neighborhood anonymously, which led her to meet “incredible” people in an atmosphere where there was “a community spirit because there wasn’t so much money around, nobody had much to lose.”

In the second part of the video, Cindy Sherman remembers that SoHo was a small town art world “in a good way.” She was originally daunted by the idea of moving to SoHo from Buffalo until she saw a famous artist on Mercer Street carrying groceries. “I suddenly thought, wow, this is not so intimidating after all. He’s this famous celebrity artist just getting groceries like it’s any old city.” Though New York is certainly not just any old city, after that encounter, Sherman decided she was ready to move to SoHo.

The two building blocks that comprise any neighborhood are a built environment and the people who inhabit it. In the case of SoHo, artists lived and worked in the large manufacturing spaces in SoHo’s cast iron buildings. Today, when so many people work from home, working where you live is not such an unusual notion, but back in the 1960s, when artists adapted these large spaces to make their work and lived in them (illegally) as well, the notion of live-work was novel, but made perfect sense in the everyday life of artists for whom life was art and art was life. And although many artists tend to work alone, the cluster of approximately 250 cast iron buildings in SoHo created a “small town” within our very large city, where artists could mingle with kindred folk who shared an affinity for creating and were thus able to exchange ideas and inspire each other. Every day occurrences, going to the supermarket, the dentist, Fanelli’s, or just walking down the street, were an integral part of the process of creation for many loft dwellers once upon a time.

This is what made artists’ SoHo such a magical place for that brief moment in time, a place that has been mythologized in the public imagination and a place that many have tried, and failed, to recreate. Not only was each artist who came to SoHo permitted to live their work, they were mixed in among many others who did the same, separated from the rest of Manhattan through benign neglect. As long as SoHo was “dirty, dark, poor, and dangerous,” the city looked the other way. As the population of SoHo changed, however, as people for whom clean, well-lit, wealthy, and safe spaces were a priority and making art at all costs was not, a fragile bubble burst and small town SoHo became integrated into the big city.