…things like memory, how one uses memory for one’s own purposes, one’s own end, those things interest me… deeply.

—Kazuo Ishiguro

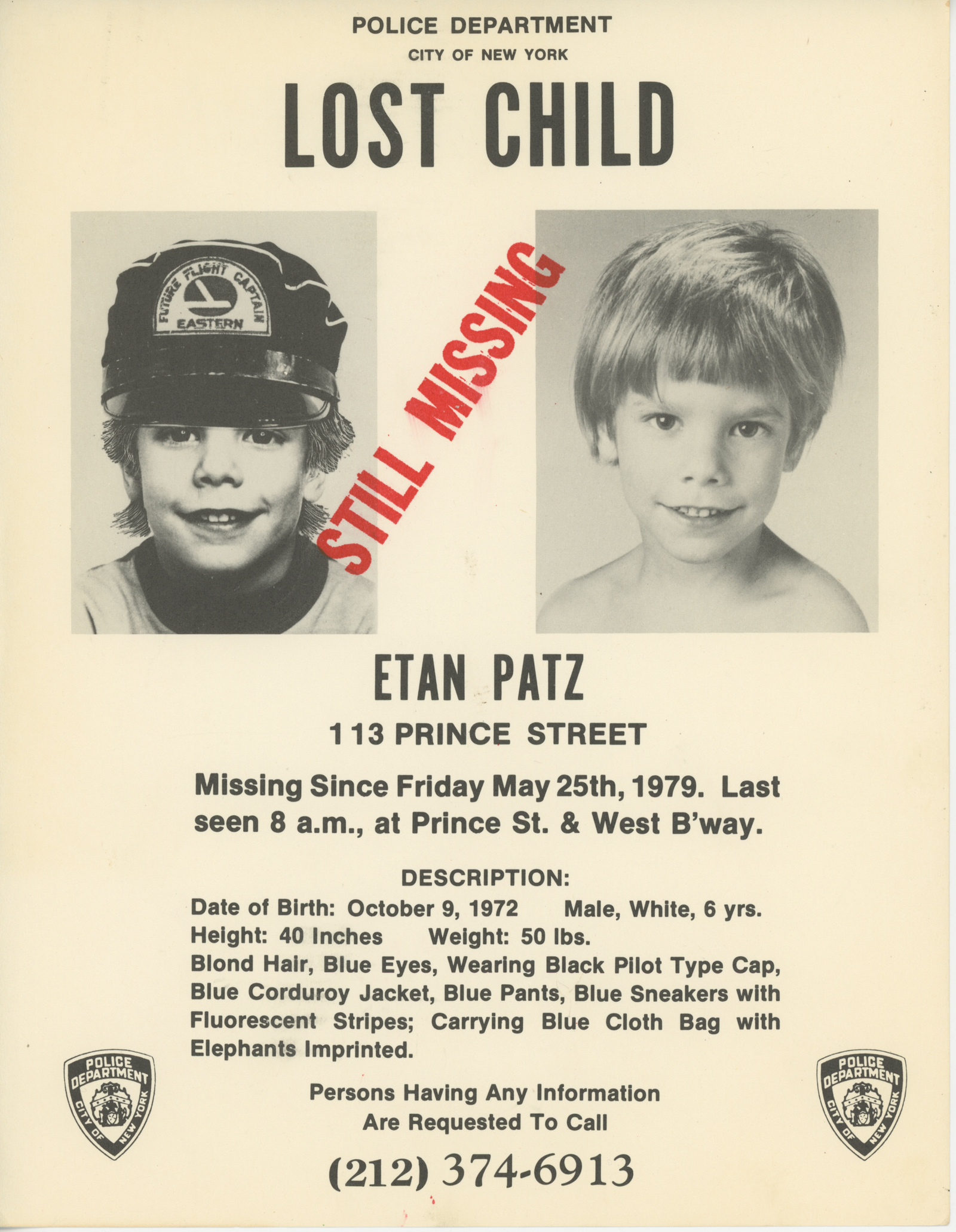

Some of you may have noticed that I have never written about Etan Patz on this blog. A gaping hole, if my mission is to record SoHo memory. I “neglected” to write about him for a number of reasons. First, out of respect for his family, not wanting to add to the no doubt numerous daily reminders of his absence. Also, because I did not know what to say. Nothing I wrote could possibly sum up the event, the time, the place, the emotions, the lack. But after the FBI and NYPD reopened the case of Etan Patz’s 1979 disappearance and descended upon the corner of Prince and Wooster last month, our neighborhood (once again) became the center of a media circus and I feel that I should now put in my two cents, an ante much smaller than the deluge of on-the-scene reporting of late, but worth something, I hope.

Initially, when I was contacted by The New York Times, The Post, WNYC, and API, among others, as the resident expert on SoHo history (who knew?), I was reluctant to speak to anyone. I did not know if I had anything helpful to say, but after being encouraged by someone I truly respect to do my civic duty to help the press get the story as accurate as possible, I agreed to do the interviews.

I was asked many things. What did the basement at 127 Prince, the site of the investigation and our childhood playgroup, looked like? What did I remember about Etan? I was also asked repeatedly if, after his disappearance, my parents became more protective of me, if my life had changed because of it. The answer I suspected they wanted, judging from recent press coverage of the story, was, yes of course they never let me out of their sight after that and I lived in fear for the rest of my childhood. But, the truth is, I do not remember being kept off the streets or public transportation, and neither does my mother. Of course, we are all tense and super-duper cautious, but my parents still had to work and I still had kid things to do, and I remember walking to school by myself and taking the public bus to the Y after school by myself (not to mention flying to Japan with my sister, Mimi, by ourselves in the summer of 1979 when I was 10).

I did not wish to in any way lessen the gravity of this tragedy. I did not want to imply that Etan’s disappearance was not an earth-shatteringly sad and frightening event. I did not want to reflect poorly on my mother’s parenting skills. Nor did I wish to alter my memory to suit the story. Some parents remember keeping their children under lock and key. I spoke to one father who said that he watched his kids like a hawk. But many others remember that, no matter how much we wanted to turn back time, life went on. A parent remembers:

The matter of Etan — whether or not to speak to the press, etc — has left an indelible mark on me. My shame at helping Stan and Julie [Etan’s parents] for a few weeks and then going on about my life, the fact that our kids … just went along, as things do, while Stan and Julie endured such pain. I guess nobody can afford to devote their lives to the pain of others. We each have to endure our own pain and make our way in the world as best we can. We make room for tragedy, then we close the curtain so we can continue with our own trials, our own worries, our own need to make a living, to see our children thrive.

In an Associated Press article entitled, “After NYC Boy Vanished, Era of Anxiety Was Born,” a reporter quotes me at length, but glosses over the fact that I specifically said I did not remember being (over) protected, that I walked the streets rode the subway alone after Etan disappeared, and that my mother does not remember keeping me at home or guarding me from the world outside. We were undoubtedly changed by Etan’s disappearance, but we coped, sometimes by whistling a “happy” tune:

Ohta’s mother brought her up with the rose-colored idea that Etan was still out there somewhere, alive. She has clung to this story, all the while knowing it was probably not true. “That idea sort of has been shattered,” she said last week after the latest search for his remains began. “And it’s a little hard to take. You try to cope with something the best you can. And if you don’t know, you can make up stories.”

Yet it wasn’t as simple as boy disappears, appears on milk carton, America’s innocence is lost. We did the best we could, and we did not have the luxury of distance, geographical, temporal, or emotional. This case changed the way we look at the world, but it is the world we were dealt, and we had no choice but to continue to live in it, to carry the past into the future.

I saw Julie the other day. As she passed, she said hello and smiled an ambiguous smile. I was with my daughter and some other children. In that one instant, Julie inspired in me overwhelming sadness, fear, rage, guilt, admiration, respect, and love. So there’s my two cents.