I recently received an email from the writer Laura Tucker who told me that she had used stories from SoHo Memory Project as part of her research in writing her new middle-grade novel All the Greys on Greene Street, set in 1981 SoHo. I couldn’t put it down. I read it in one sitting!

The New York Times called All the Greys on Greene Street “a brilliant debut. . . . This novel is a richly textured delight.” From the book’s press release:

Twelve-year-old Olympia is an artist—and in her neighborhood, that’s normal. Her dad and his business partner Apollo bring antique paintings back to life, while her mother makes intricate sculptures in a corner of their loft, leaving Ollie to roam the streets of New York with her best friends Richard and Alex, drawing everything that catches her eye.

It was such a treat to read Laura’s book! I grew up in SoHo, and I was twelve years old in 1981, and the book is full of details specific to a SoHo childhood at that time: sword fighting with cardboard tubes, hanging out on the fire escape, sneaking around unnoticed at loft parties. All you “SoHo kids” who are now probably parents of twelve-year-olds, this book will take you back to the good ol’ days when SoHo streets were our playground.

Laura kindly agreed to do a brief Q&A with me and also supplied me with an excerpt from her book (see below). Although All the Greys on Greene Street is categorized as a middle-grade book, I think all audiences will enjoy seeing SoHo through Olympia’s eyes and will sympathize with her struggles to take care of her depressed mother as she hunts down clues to find her father, who mysteriously disappears in the middle of the night. A mystery, a coming-of-age story, and a SoHo memory wrapped up in one!

For more information about All the Greys on Greene Street click here.

Q&A with Laura Tucker

Q: What role does SoHo play in the story?

A: SoHo is a huge part of the book—one reviewer said the setting functions as another character, and I think that’s true.

Certainly, the sense of place is especially important because Olympia, the twelve-year-old protagonist of my novel, is an artist. I’ve always been fascinated by those moments when a group of artists or writers are working in close proximity, inspiring one another and stealing from one another and fighting and falling in love, creatively and otherwise.

Which led me to the question: What if you were an artistic kid, growing up in one of those hubs?

What’s different when a talented kid knows working artists? What if she didn’t have to explain why her work is important, but was instead racing gleefully to keep up? What if she didn’t just have access to decent supplies—but to Pearl Paint, all six floors of it, not to mention a professional restoration studio, and a community of adult artists who take her work seriously?

You’d know better than anyone, but it seems to me that the kids who grew up in SoHo when it was still a center of the art world had a very unique, everyday relationship to art. It wasn’t fancy, or something you had to travel to see: it was what people in your neighborhood did, sometimes on the wall of the parking lot across the street from your house.

It’s not surprising to me that a lot of those kids are still involved with art in one way or another.

Q: How did you get the details in the book so spot on?

A: I’m a researcher by trade and by inclination, and researching this book was the most fun I’ve ever had. I can’t tell you how delightful it is to hear that I got some part of it right!

SoHo Memory Project was a fantastic resource, and I was hugely grateful to you for it. Helping people like me to get it right is just one reason that an archive like yours is so important.

SMP aside, I tend to cast a very wide net when I’m researching. You never know when you’re going to stumble on the everyday, lived detail that will make the whole thing feel true. This is probably why I tend to be attracted to everything on the edges of the official, sanitized version—the first drafts, and journal entries that weren’t produced for public consumption at all; the backgrounds of the photos; the pocket litter and paper ephemera that someone shoved in a drawer and forgot.

I did read a lot of first-person accounts—memoirs and oral histories by artists and kids raised by artists, as well as by people who grew up with a parent who was living with mental illness, and parents who raised kids while they were struggling with depression. I looked very closely (okay, obsessively) at photographs, both online and in books. I went to see a lot of art. I watched every documentary I could find about artists who worked in SoHo and elsewhere. I even looked at real estate listings.

And I developed a bad habit of cornering people at parties, with what must have seemed like terrifyingly specific questions. . . .

The following is an excerpt from All the Greys on Greene Street, in which Laura brings SoHo to life:

Five for a Dollar

Upset as I was, my stomach growled again as I followed Apollo out of the studio.

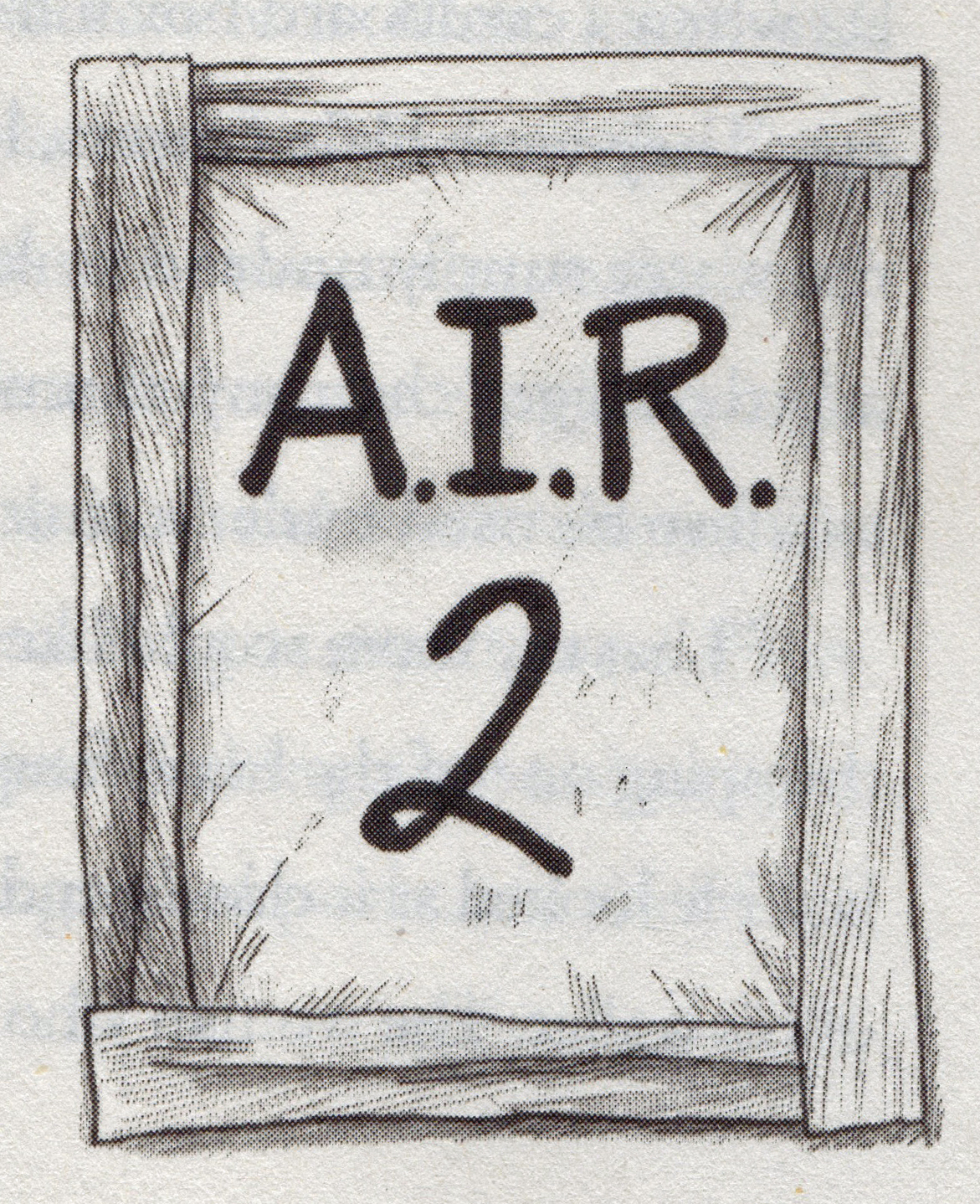

I waited as he bent down to pick up a ball of newspaper and some other scraps of trash that had blown into the little tiled vestibule at the bottom of the stairs. He passed them to me to hold while he pressed down the ratty silver duct tape securing the artist-in-residence sign to the front door of the building.

The A.I.R. sign is there to let firemen know that our building isn’t abandoned, or a factory—empty at night. Some of the A.I.R. signs you see around SoHo are official looking, white letters embossed onto plastic plaques like the name plate outside the principal’s office at my school. But the sign on our door is a piece of cardboard box wrapped in plastic and duct-taped to the window, A.I.R. 2 written in thick black marker on the front. The two is because we live on the second floor.

Maintenance complete, the two of us walked down Greene Street toward Canal. Even though it was almost dark, there were very few lights on in the buildings we passed. The lofts near us that don’t have factories or artists in them are mostly used for storage. Bundles of old rags and paper, and not very many people around to call 911 when they smell smoke? There’s a reason that firefighters call my neighborhood Hell’s Hundred Acres.

We turned left at the corner of Canal, and the subliminal mind control I used on Apollo must have worked, because he looked across the street at the art supply store, but he didn’t cross to go in. I love Pearl Paint, too, but I was way too worn out and hungry for an hour of small talk about solvents.

We did stop to look at the boxes outside the hardware stores on Canal. Apollo was standing over a tray filled with skinny spatulas when a cardboard box filled with tiny brass objects caught my eye. They were little faucets, like the red ones you use to turn off the water supply under a sink, except brass and miniature—only a little bigger than my thumbnail. Too big for a dollhouse, too small to be used under a sink for real.

“I bet my mom would like these,” I said, breaking the silence and dropping one of the brass faucets into Apollo’s palm. “Five for a dollar.” He looked at it closely and then nodded and pulled two bills out of his wallet. The woman who had come out of the store handed me a small brown paper bag, and I counted ten of the tiny faucets into it.

My mom and my dad and Apollo and Alex’s mom all met at art school in Brooklyn, even though my mom and Apollo are the only ones still making art. My dad can draw anything; he’s the one who taught me. But now he only works on other people’s art.

My mom, on the other hand, can’t help but make things. Over breakfast at a coffee shop, she’ll knot napkins and the wrappers from our straws, using a drop of water or coffee or juice to mold the paper. By the time we’ve finished our bacon and eggs, she’ll have turned the whole table into a sculpture garden. One time, she didn’t like a book I brought home from school about the first Thanksgiving, so she cut it up to make a collage about the Pilgrims stealing land from the Wampanoag and the diseases they brought that practically wiped out the tribe. Another time, my dad asked her to sew a button back onto his favorite shirt, and she stitched geometric patterns, wild like vines, up the sleeves instead. The next time he wore it, a lady on the street offered to buy it off him for a hundred bucks.

Apollo and I turned off Canal Street onto Mott. Little kids chased one another up and down the narrow block while moms squeezed melons and grandpas smoked between the parked cars. We stopped at a fruit and vegetable stand where Apollo bought a bag of the tiniest mangos I’d ever seen, the size of walnuts. The green beans right next to them were as long as my forearm. Honestly, the size of them is the only special thing about them. We get them at Wo Ping with garlic and ground pork, and they taste exactly like the short kind.

My dad says observation is a muscle that artists have to build. You have to choose the details you include in a drawing, and to choose them, you have to see them. “Don’t draw a cartoon of what you think a strawberry looks like,” he’d always tell me. “Look at a strawberry, then draw what you see—not what you think you see.”

So I practiced my observing. Most of the stores on Mott had big metal garage doors that rolled up in front instead of windows, making it hard to tell where the sidewalk ended and the stores began. At one place, whole fish stared back at me from beds of melting ice, sparkling purple-brown and blue and silver underneath metal hanging scales. Pink shrimp, cooked and cleaned, lay next to grey ones with their heads still on. At the back of another store, I saw an aquarium crowded with silvery brown carp, and another one, the water dark with eels.

I looked into a woven wooden basket almost as tall I was, standing by the curb. Inside were hundreds of live crabs. The slow chitter of their claws moving over the hard bodies of the others made me shiver. They had greenish-greyish-brown bodies, and beautiful blue claws.

“Lapis,” I said out loud, and Apollo smiled.

Lapis lazuli is the stone you grind to get ultramarine, the most beautiful and the most expensive of the blue pigments. It used to cost so much that Michelangelo had to leave a corner of one of his most famous paintings unfinished because he couldn’t afford the paint. Lapis is expensive now because it comes from Afghanistan, which is in a war with Russia, so it’s hard to get. Apollo has some, though. And before you grind it into ultramarine, lapis has streaks of grey and brown and white in it, the same colors as the crabs.

Apollo said, “They tell me that in Old San Juan, the streets are cobbled with bricks cast from the waste that comes from making iron, brought to Puerto Rico three hundred years ago as ballast in the bottom of Spanish ships.”

The stones they used to make New York’s cobblestones came as ballast on ships from Belgium. My dad told me that.

“The iron made these bricks blue—all different shades. Imagine! Ordinary streets, paved in cobalt, azure, indigo.” Apollo smiled down at me. “Perhaps you and I will go to Old San Juan one day, and dance on bricks the color of a blue crab’s claws.”

I looked at the crabs crawling on top of one another, going nowhere, and wished I could tell Apollo about my mom. But the emptiness on her face when she said she couldn’t go back scared me into silence.

Maybe—if things didn’t get better, and my dad wasn’t back yet—I could tell Apollo. Maybe he’d let me stay with him for a while.

The two of us stood there for a minute more, watching the crabs.

“I didn’t know they had cobblestones anywhere but here,” I said finally.

Apollo nodded. “Paris is famous for them, actually.”

Paris. In France, where my dad was.

We were quiet the rest of the way to Hwa Yuan.

Laura Tucker has coauthored more than twenty books, including two New York Times bestselling memoirs. She grew up in New York City around the same time as Olympia, and now lives in Brooklyn with her daughter and husband; on Sunday mornings, you can find her at the door of Buttermilk Channel, one of their two restaurants. She is a cat person who cheats with dogs. All the Greys on Greene Street is her first novel.