“At 112 there was a crackup of context and art, so much so that, to the casual observer, art and context were indistinguishable. Of course we knew which was which.”

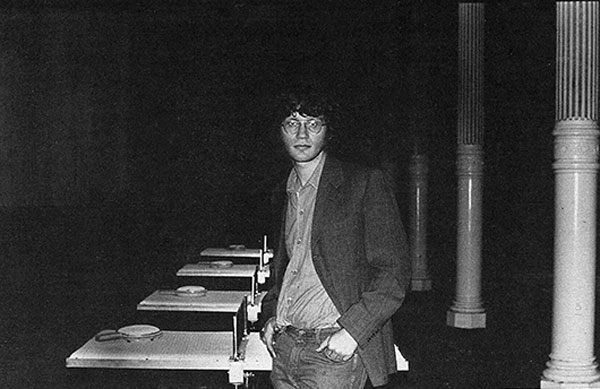

Artist Bill Beckley thus described 112 Greene Street, a difficult-to-define (un-)gallery, what some have called an experimental art space or a workshop, created in 1970 by Jeffrey Lew, along with Gordon Matta-Clark and Alan Saret. Sadly, Beckley passed away last month at the age of 78. Though he had a long career that spanned many decades, he is perhaps best known for his installations and performance pieces that were shown during 112 Greene Street’s early years, when its founding artists invented new ways of approaching art, performance, and exhibition that had a lasting impact on how we view art today.

“When I first saw 112 Greene Street with Rafael [Ferrer] in the summer of 1970 it was strewn with debris from its past existence as a factory,” Beckley wrote in The Brooklyn Rail in April 2013. “This was not the clean white room so easily used to recontextualize; often, you could not tell the art from the rubble.”

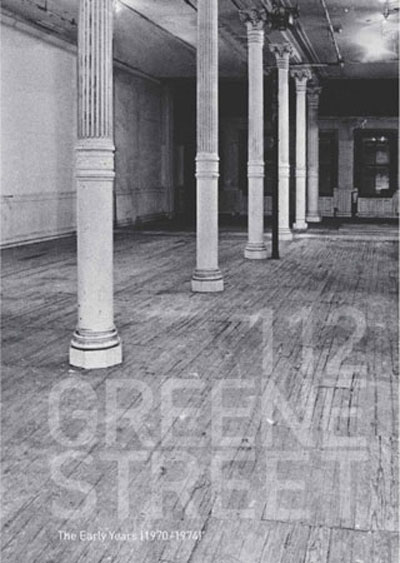

What follows is a tribute to Beckley through excerpts from his writings about 112 Greene Street. There are a few excellent and much more comprehensive resources on the gallery and its legacy, including Jessamyn Fiore’s 112 Greene Street: The Early Years [1970-1974] and 112 Greene Street A Nexus of Ideas in the Early 70s by Solomon Contemporary. These were published in conjunction with concurrent exhibitions mounted in New York City at David Zwirner Gallery and Salomon Contemporary in early 2011 that featured work from 112 Greene Street artists, including Beckley. White Columns also has an excellent and extensive 112 Greene Street archive. I have drawn from these publications, as well as articles by Beckley, to present a bricolage of his memories of 112 Greene Street–one person’s firsthand account of a place and time that impacted so many.

In his oral history for 112 Greene Street: A Nexus of Ideas in the Early 70s, Beckley describes the zeitgeist that gave birth to 112 Greene Street:

I met Gordon Matta, Alan Saret, and Jeffrey Lew in the summer of 1970, through Rafael Ferrer, a friend of my former teacher, Italo Scanga. Something was in the air. Younger artists were breaking away from the Minimalist aesthetic as defined and practiced by Frank Stella, Brice Marden, Robert Ryman, Carl Andre and Donald Judd. It was not because we didn’t respect their art; we just didn’t want to be confined by their aesthetics. What happened at 112 Greene Street in 1970 was the antithesis of Minimalism. It did away with the much of the orderliness, the geometry and the mathematical progressions of Minimalism, but, like Minimalism, our work stayed clear of illusionistic painterly space.

In “112 Greene Street–Spaces Interior and Exterior,” an article Bill Beckley wrote for the Brooklyn Rail in April 2013, he describes the gallery’s founding:

[I]n October of 1970, an artist named Jeffrey Lew opened the ground floor and basement of 112 Greene Street. Actually there was no official opening. The doors were simply unlocked and stayed that way.

It was a messy aesthetic. Broken glass and industrial waste littered the floors. The basement was frightening. Except for the occasional merchant of cocaine and hashish, there was no dealer present to officiate over the sale of art. In fact, there was not even the notion of a sale.

In the same article, he catalogs some of the work one could find at 112 Greene Street:

At 112, one could hardly tell the art from the space or visa versa. A brief inventory of work could include: a thin metal tray setting on the floor where Gordon grew algae, and his poetic dancing-in-the-rain dumpster piece pilled with open umbrellas. 112 extended to the outdoors; Vito Acconci blindfolded himself and huddled in the basement, swinging a stick whenever he heard footsteps on the stairs. Vito was an art mugger, when there were still street muggers in SoHo (ah, nostalgia!). Any gallery visitor was a possible muggee. Rafael Ferrer’s installation—a bucket, a rope, a sheltering cloth, evoked a homeless abode, or perhaps it actually was an abode; Barry Le Va’s nine cleavers planted in the wall at equal intervals alluded to a minimalist aesthetic but evoked dead chickens and serial killings; Louise Bourgeois’s multi-phallic homage, “The Destruction of the Father” nudged us away from our patriarchal past; Suzanne Harris’s megalithic dance contraption, “The Wheels,” composed of revolving eight-foot wooden gears, provided dance sites for the nimble. Suzanne also danced with Yvonne Rainer’s Grand Union dance group, named after the grocery store on LaGuardia just above Houston. Like the art at 112, you could hardly differentiate dance from common human activities like walking, sitting, and sleeping; George Trakas’s beautiful sculptures, constructed from glass and wood, bludgeoned through a hole from first floor to basement, creating a unified upstairs downstairs.

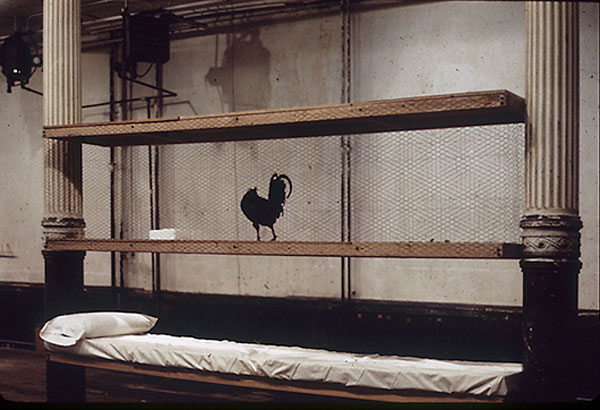

Here, in an oral history included in Jessamyn Fiore’s, Beckley describes one of his own works that he included in 112 Greene Street’s inaugural show:

The rooster for my work Rooster, Bed, Lying came from Pennsylvania. The structure of the piece was a reference to minimalism – the vertical wall pieces of Donald Judd, the lower of the three platforms supported an elongated bed complete with mattress and pillow.

It was important to me that the viewer could actually sleep on it. If you did, though, you might be awakened by the live rooster who paced around on top of the second platform. The third – which was the same size as the other two – completed the henhouse, or more correctly, the cock house, because chicken wire was stretched between the two upper platforms.

Of course, the live rooster was a reference to the famous piece with the dead rooster by Bob Rauschenberg. But, my rooster did at some point become a dead rooster. An artist who shall remain nameless decided at this time to dye a pile of rope with a toxic substance, and in the wonderful spirit that was 112, dumped it beside my rooster piece. The rooster first stumbled in circles and then fell, poisoned by the toxic fumes. I feel guilty to this day. (pp. 38-39)

And finally here, Beckley reflects on the rise, and eventual fall, of the spirit of 112 Greene Street:

The closest comparison I can think of to 112 Greene Street is the first gropings of love, when everything you do together is fresh and new, when jealousy and ownership have not yet entered the picture. There is no pretense, no agenda, and no cynicism. You don’t know where it’s going, or what will come of it. All you want to do is fuck. But this balance of sex and naiveté is difficult to sustain.

I stopped showing there in 1973. And I knew the scene was over when in 1976 I witnessed Gordon’s identical twin brother, Sebastian, jump out the window of Gordon’s loft right above mine at 155 Wooster Street. Gordon died of cancer a couple years later. By then, the spirit of 112 Greene Street had already departed.

As the neighborhood developed, costs increased, and 112 Greene Street, still under the direction of Lew, received a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1973, the same year Beckley decided to move on. With a grant, especially a government grant, comes accounting and accountability. The funds kept the gallery open, but they also required the gallery to become formalized. In this process, the excitement and spontaneity of the early years was lost. In 1976, Lew cut ties to 112 Greene Street, but other artists in the community kept it going, as a nonprofit organization called White Columns that still exists today.

The works exhibited at 112 Greene Street, the installations and the performances, were ephemeral, but traces of the gallery’s legacy remain, through the existence of White Columns (and its rich archive) and through the legacies of its founding member artists, including Bill Beckley’s.

Beckley sums up the paradox of 112 Greene Street when he spoke to Randy Kennedy in 2012 for The New York Times: 112 Greene Street was, … both a freedom ‘to’ and a freedom ‘from,’… Both a positive and a negative liberty. That balance is difficult to maintain even for a moment’s passing, let alone an era.”