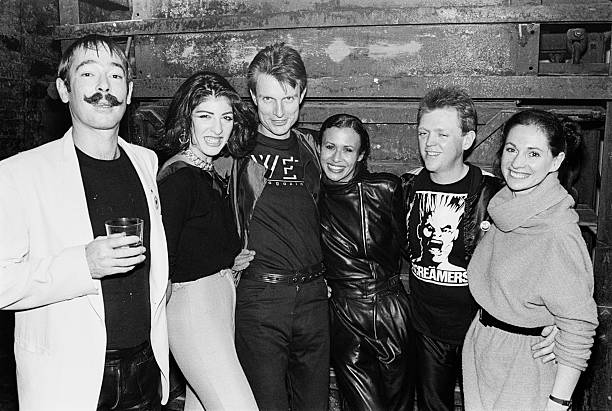

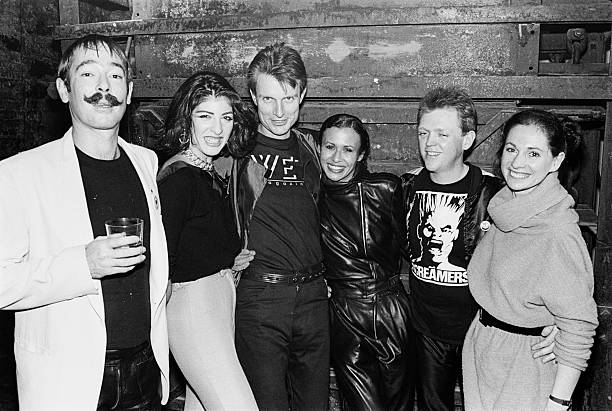

Rudolf Pieper, Jim Fourrat and friends (including Janis Savitt) at Pravda, 43 Crosby Street (image: Allan Tannenbaum)

“We should have seen the end coming because in ’79 this club called Pravda was scheduled to open on Crosby Street,” says writer and music critic Peter Occhiogrosso in a recent conversation with the late Stephen Saban, legendary chronicler of New York nightlife, with whom he worked at the SoHo Weekly News. The “end” to which Occhiogrosso refers, is the end of artists’ SoHo.

Pravda, an arts venue or nightclub (depending on who you ask), was a collaboration between stockbroker-turned-restauranteur-turned-nightclub-owner Rudolf Pieper and Jim Fourrat, the duo behind Danceteria, one of the hottest New York nightclubs of the 1980s. Slated to open in late-1979, Pravda opened for one night, November 8, and for one night only. Regardless of its ill fate, however, the venue and its failed opening symbolized a sea change in SoHo, as it straddled a line between the SoHo art world of the 1970’s that had already begun to fade and the glitzy glamour of the 1980’s fame and fashion world to come.

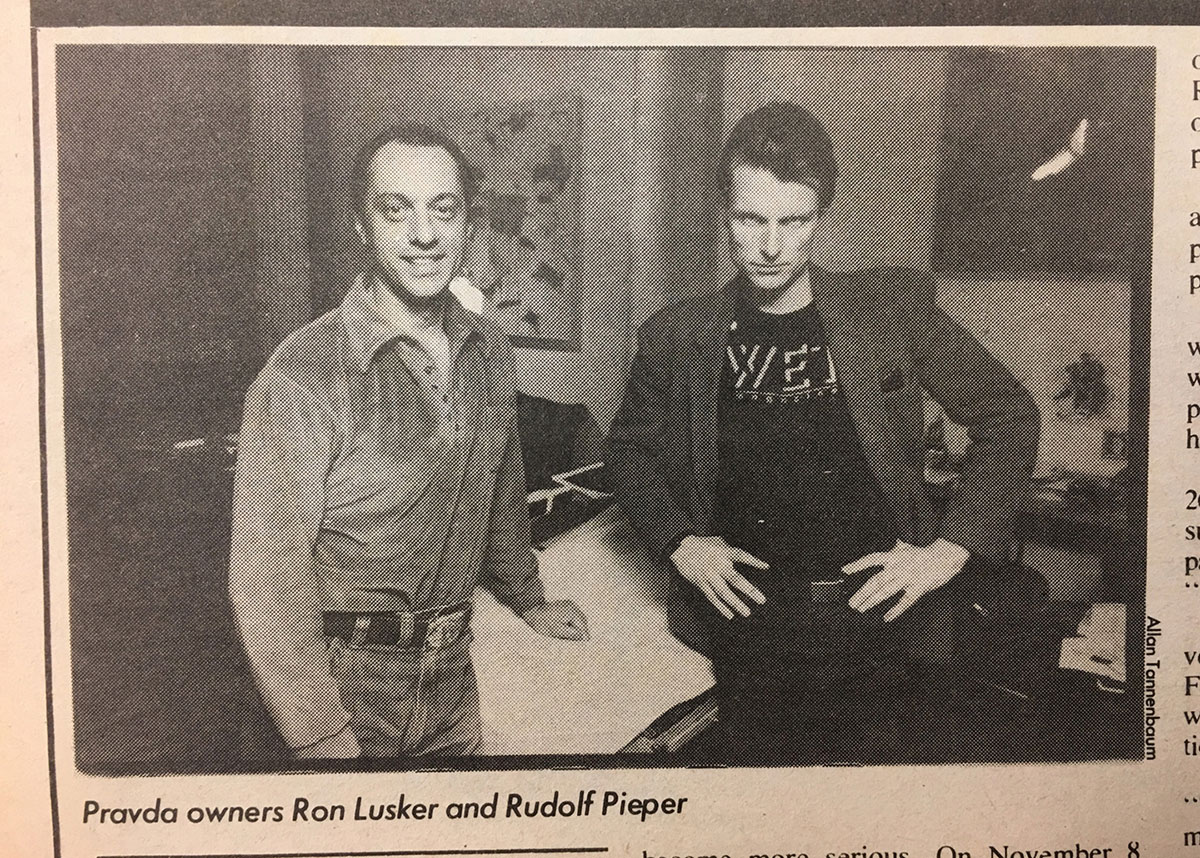

Ron Lusker and Rudolf Pieper of Pravda (photo: Allan Tannenbaum for SoHo Weekly News)

Residents of SoHo, as well as New York club scene insiders, had heard about Pravda long before it (almost) opened. The was a buzz around the project from the beginning. Fourret was the booker for Hurrah, a successful dance club on 62nd Street. It was rumored that Sean Cassette (who originally introduced Rudolph and Fourret), a hot British deejay who played punk music, was coming on board. Even more buzz-worthy in SoHo, however, was Ron Lusker, a partner in the enterprise, who rubbed the community the wrong way from the get go. Lusker had “managed to insult, alienate and, in many cases even threaten, just about every individual and agency in the community,” writes Alan Platt in a December 1979 article for the SoHo Weekly News.

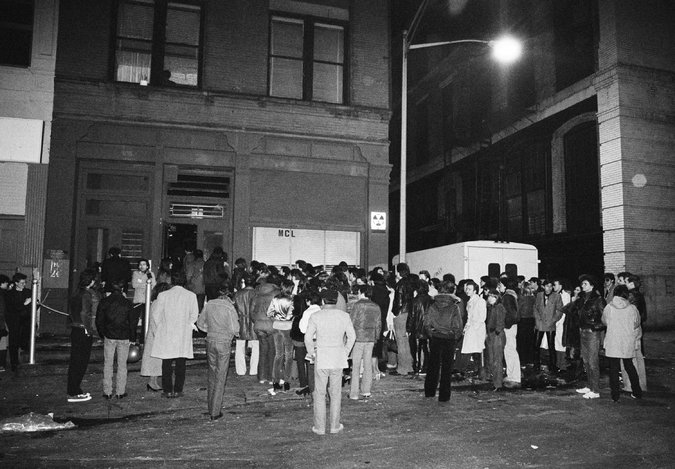

Crowd in front of the Mudd Club, 1979 (Image Bob Gruen via: nytimes.com)

Although Pravda was proposed as an avant-garde artists’ cabaret with live music (Human League and Lounge Lizards were on the slate), a deejay who would play what we now call “alternative” music, and a daytime art gallery (Ken Tisa and William Coupon were to have inaugural exhibitions), the community was worried that it would become another Mudd Club, a venue for underground music in Tribeca where rowdy clubgoers disturbed its neighbors at all hours of the night. Despite a soundproofing system at Pravda designed by sound engineer Jack Weisberg that was to prevent any sound leakage, concerns abounded.

The interior of Pravda was rather slick for an arts venue of that era, described by Occhiogrosso as “Nouveau Bauhaus with bars that jutted out at strange angles like the prow of a ship.” Much money was invested in a sophisticated sound system and state of the art lighting to feature three floors of performance art, live and recorded music and gallery shows. It did not resemble other typical avant-garde art spaces that were more DIY and AS IS. This space was DONE UP. This space looked like a nightclub.

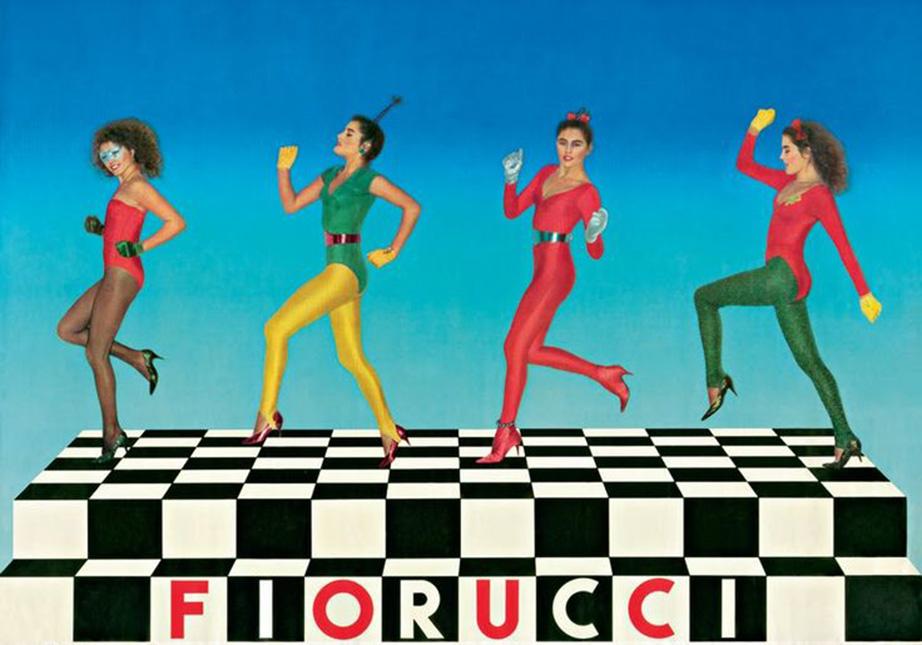

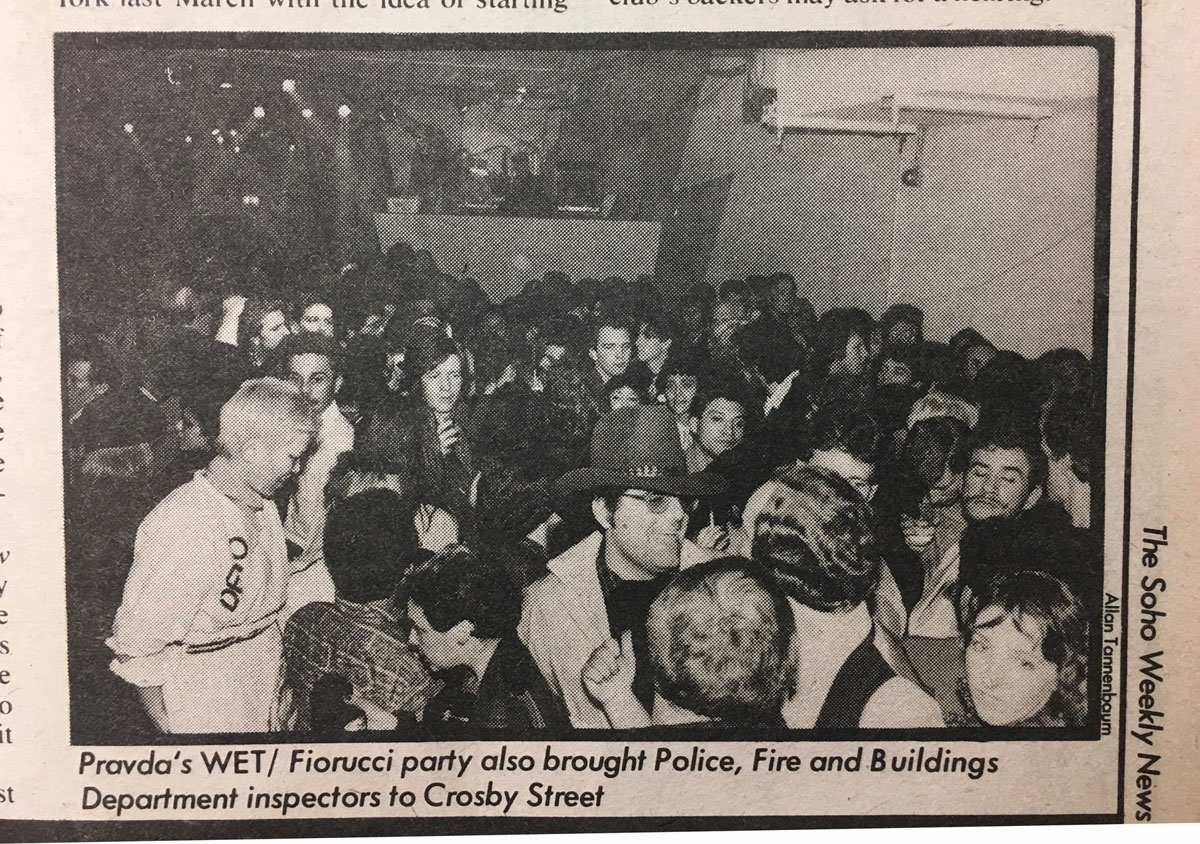

The Fiorucci+Wet party at Pravda on November 8, 1979 (photo: Allan Tannenbaum for SoHo Weekly News)

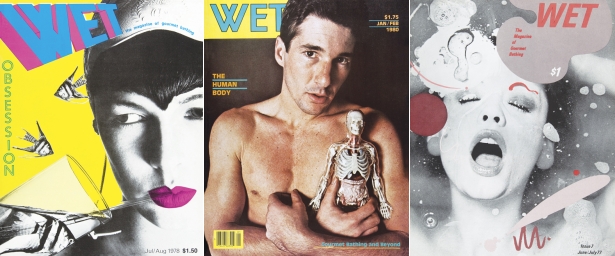

And then November 8 happened. Once the construction for Pravda was finished, but before it was to officially open, Fiorucci, the then “it” fashion “concept store” with fans such as Cher, Elizabeth Taylor, and Jackie Onassis, threw a pre-opening fashion show and party for Wet: The Magazine for Gourmet Bathing. What exactly is gourmet bathing? Nobody was sure. The magazine itself is described by Steven Heller in The Atlantic as a “screwball arts publication that ended up influencing a generation of designers, writers, and editors—and maybe even a few bathers” and “an archetype for a new subgenre of stylish, irreverent magazines.” With a list of contributors that included Matt Groenig and Herb Ritts, Wet, like Fiorucci, was a hip new trendsetter.

A Fiorucci advertisement from the late 1970s

That night, before the sun even went down, hundreds of people showed up for the party on quiet Crosby Street causing a scene the likes of which SoHo had never seen. Once the crowd was admitted, the narrow staircases (left over from the building’s factory days) caused a logjam in the rush for the open bar. FDNY, NYPD and the buildings department were called in by neighbors. Pravda was shut down, never to open again.

Covers from Wet: The Magazine of Gourmet Bathing (image via The Atlantic)

In Tim Lawrence’s Life And Death On the New York Dance Floor, 1980-1983, Pieper is quoted as saying “The neighbors wanted to keep SoHo as an exclusive artistic enclave… They were too fucking serious and did not understand the concept of uniting art and nightlife.”

Mary Breasted, writing for SoHo Weekly News in 1979, comments, “How much trendiness can Soho bear before it destroys its original purpose and sends its artists fleeing to new neighborhoods? Can a community reach a point of critical mass in “in-ness”?”

In the end, bureaucratic and financial problems as much as neighbor complaints prevented Pravda from ever (re)opening. “The opening was also the closing,” laments Saban to Occhiogrosso. Yet on the night of November 8, in the twilight of the 1970s, the tragicomedy that was to be SoHo in the 1980s played itself out in a brief few hours. That night, the avant-garde arts venue was overrun by the new guard (the apres-garde?) of popular culture, and this incident would prevent said arts venue from ever seeing the light of day (or night) again.