By Nim Macfadyen

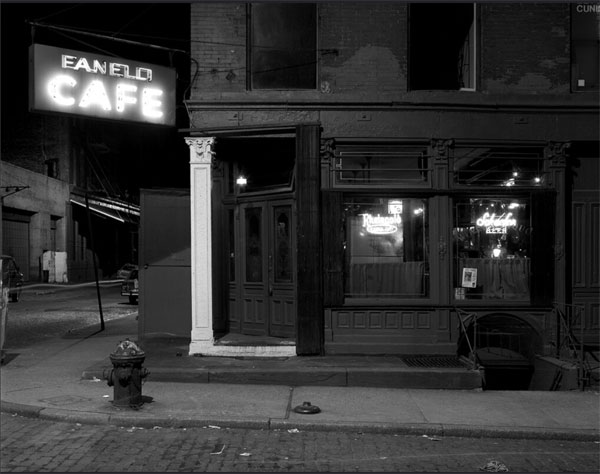

Every young, aspiring artist ought to have a corner table or bar stool in some sweet dive where he can while away a decade, a post-youth period spent steeped in the convivial yammerings of his peers. Art schools and writers’ workshops, remote and rarefied, may introduce students to the art of loafing in coffee shops and tap rooms, laying a tame and coddled foundation for this sort of socializing, but the real thing lies just down that scarred and cobbled street, past the iron bulkheads and twisted trash cans, on that corner there beneath the neon sign.

I had the good fortune to be ushered through a set of mysterious, etched-glass doors and into the wondrous cacophony of creative mayhem that was Fanelli’s by a well seasoned regular. Here, within the wintersteamed windows lay a warm, glowing haven where one could escape the city’s solitude, it’s loneliness, and the often staggering blockage that came from trying to force paint on to paper or words to the page. And even then, in the winter of 1979, just before the hordes descended – long before the double-deckers and boutiques – I was a latecomer, propping myself up at the waitress station, nursing a dollar-a-bottle, longneck Bud and absorbing the end of an era.

My friend Phil Smith first brought me in, introduced me to Larry, the bartender and a string of regulars occupying the stools in what I would come to know was a fairly precise order: Phil, closest to the waitresses and pay phone, then Kenny, Charlie, sibilant, turtlenecked Tom who reminded me of Liberace, duck-tailed Stewart, who looked like an aged and battered James Dean, and so on down the line. This order rarely varied, was well cemented by six o’clock, and woe be unto the casual pub-crawler who might mistake an empty stool for a vacant stool; who, upon feeling a sudden congestion and loss of personal space together with a blast of hot, rancid keg-breath to the back of the neck might move sheepishly down towards the end of the bar where the stools had less propriety.

Places were marked by cigarette packs anchoring small stacks of currency from which Larry would draw, pouring rounds without having to be asked. More often than not, this crowd enjoyed the pleasure of the House, drinking free for hours and leaving the stack behind.

In those few years before he sold the place, Mike Fanelli, in a floor-length apron rolled high above his waist, often worked the bar himself into the early afternoon. A simple lunch, maybe a bowl of Bolognese or Minestrone with a basket of bread, was served at the five or six, checked-cloth tables along the wall opposite the bar, or in the “Ladies & Gents Sitting Room” in the back beyond the waitress station.

Mercifully forgoing any temptation to hang the patrons’ work, the walls were adorned, salon-style, with action shots of bygone boxers, framed and autographed by the likes of Rocky Marciano and Jake Lamotta. It was rarely crowded at lunchtime; neighborhood workmen still ate there, mixing with gallery staff, like Phil, a few career inebriates at the dark end of the old, mahogany bar and a handful of old timers, friends of the Fanelli’s who’d been regulars since they took over the place in 1922.

In these soft and quiet daylight hours, filtered through smoke and floating motes of vintage dust, the bar took on a timeless quality, every detail unchanged and available as a Hopper painting: the pressed tin ceiling, once lead-white and now, like the 1930’s rubber duck behind the bar, a satin-rich, pale mahogany, smoked like a ham in fifty years of nicotine. The waitress station at the back of the room had it’s own, smaller version of the carved bar behind which one girl usually handled lunch, brewing coffee, slicing cake or pie and setting up her service. Across the tiny-tiled, mosaic floor, beneath a television, was a phone booth where regular patrons tried to avoid taking personal calls demanding they come home. The men’s-room, notable for such memorable graffiti as, “The tundra is frozen and the caribou are running…” – a snippet of esoterica virtually guaranteed to free any creative soul from whatever mental block might ail him – stood just to the right of the phone booth.

The back room, the “Ladies & Gents Sitting Room”, had been added at some stage when the idea of serving something other than pickled eggs and pigs’ feet to workmen from the nearby Pinking Sheers Building took hold as a way of expanding business to a broader clientele. Ladies of the day, who would not have set foot in a bar, needed a place to sit and dine, removed from the spittoons and reeking urinals their men had been enjoying for generations. Another six or eight tables filled the room and the ladies-room had been carved out of an alcove to the right where a bathroom sink was only partially hidden by a curtain – rarely drawn – and the kitchen had been added beyond the sitting room.

In the crowded, bustling evenings, I’d stake my perch at the waitress bar together with one or two others who favored that spot. Beneath the sobering, Reagan-era blather of MacNeil and Lehrer one of them might suddenly slap a dollar down and nod towards the curtained sink at the entrance to the ladies room. For years, maybe decades, these guys had been betting on the likelihood of whoever had gone in there washing their hands on the way out. It was a sucker’s bet; I always wagered that they would, and I always lost.

In the soft and quiet afternoons I might sit up at the head of the bar, at the oddly short and beveled length by the front window, the better to see the goings on at the corner of Prince and Mercer. Because the edge of that bit had been inexplicably eased and beveled, you had to be careful about setting your drink down lest it fall in your lap or worse, shatter on the tile, bringing the attention of the entire congregation down upon you in the form of hoots and cat-calls.

One day, after leaving the studio early, defeated by whatever I’d been working on and unable to find a way around it, I stopped in and took a seat there by the window. Larry was already popping the top off my long-neck as I settled in and, setting the bottle down atop my short stack of singles to indicate that it was on the house he said, “You know about the edge that slopes toward you, so beware.” In the two or three minutes it took to parse this profound and meaty morsel, my creative block evaporated. I chugged the beer, left my money on the table and bolted out the door. Heading back to the studio, I could hear Larry calling after me, “Wait! Was it something I said…?”