Librarian, author, and critic Jesse Karp and I grew up in SoHo at the same time, born just days apart, but we somehow never met until our paths crossed at my daughter’s school, where he is Lower School Librarian. In this month’s guest post, Jesse looks back at how SoHo, as a place as well as an ethos, had a hand in shaping the person he is today. I think all you SoHo “kids” will relate to this story of growing up in a special place where the “forces of art and industry met and sparked a unique vitality.”

The Neighborhood That Made Me: A Childhood Formed by the Burgeoning Arts and Repurposed Industry of SoHo

by Jesse Karp

The forces of art and industry met and sparked a unique vitality in the SoHo of the 1970s. I’m a child of that SoHo, its ethos and its landscape, and that environment, maybe as much as my family and my schooling, shaped my childhood and formed the person I am now.

I attended the Little Red School House, a progressive independent school in Greenwich Village, beginning in 1974. At the time, the family population at the school was predominantly arts-centric and my own parents were an emblematic example of that, so our lives were very much steeped in SoHo’s burgeoning arts scene.

My father, gallerist Ivan Karp, and my mother, Marilynn Gelfman Karp, a sculptor and Professor of Art at NYU moved into the Silver Towers on LaGuardia Place in 1965. The apartment overlooked the stretch of West Broadway between Houston and Prince (465-469, the space that Harbs currently occupies) where my father opened the O.K. Harris Gallery – the first gallery on West Broadway – in October, 1969. Four years later, the gallery moved down a few blocks south to 383 West Broadway between Spring and Broome Streets, and my parents – now with little four-year-old me in tow — moved into a loft right across the street.

Staff and artists outside O.K. Harris Works of Art, 465-469 West Broadway, ca. 1969

The rough, unrefined energy of SoHo back in the 70s was remarkably well calibrated to its flourishing arts-centered community, which was crafting itself with a similar edginess into something quite separate from the refined, formal and well-established art culture that was based on the Upper East Side, around Madison and 57th Street. Concurrently, all of SoHo’s denizens – arts and non-arts alike — were re-molding the raw material of the industrial neighborhood into a space that fit them. Without ever putting words to it, I very much felt that sense of defining ourselves, chiseling out who we were going to be.

That feeling came right into the loft spaces of artists like John Salt, John Kacere, H.N. Han, Jake Berthot and John Clem Clarke, who were on my family’s dinner party circuit. Those spaces felt vast and malleable and you could see right before your eyes how the artists were hammering them (sometimes literally) into studios and display areas, the art splashing right off the canvases and onto the walls themselves. It made me feel a little tough, a little rough around the edges in the most exciting way, an attitude which certainly fit the necessities of living in New York’s tumultuous 1970s.

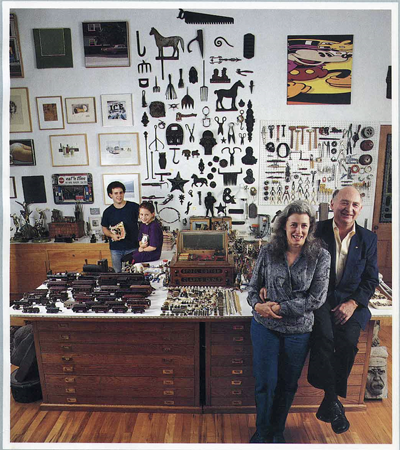

Marilynn Karp’s studio (photo: Horizon Magazine, circa 1987)

My own home (also a loft) was a different story. It, too, was filled with art, but the pieces were meticulously arranged as they were in my father’s gallery. Even in my mother’s studio space, the found objects and odd, mysterious doodads that were the constituents of her art were cataloged, arranged and curated as a museum display might be. However, even in my carefully maintained home, the remnants of the building’s industrial past played a part. So generously vaulted were the ceilings that my room had a mezzanine. I slept below, while the one hundred square foot loft served as an antique-storage and display space with a pull-out bed for guests. This was where my half-brother Ethan, eleven years my senior and living near his mom in California, would stay when he visited. There was a television up there that barely picked up a signal, but was attached to our brand-new Atari 2600 video game console. On the all-to-brief, breathlessly exciting occasions of my brother’s visits, I would often fade off to sleep listening to him play Space Invaders or Asteroids deep into the night, perfecting his skills to the point of invincibility (against a younger brother, anyway). My eyes closed, the beeps and boops left me dreaming of the impossible, joyous freedom of being older than I was.

Out on the street, my block – the west side of West Broadway between Spring and Broome – was a true wonderland of adventure for my friends and me, and later my sister Amie, who was born in 1980. The loading docks, platforms, sunken basement doors, iron railings and squat, jump-downable stairways left behind by the neighborhood’s former life as a manufacturing district became my daily – sometimes hourly — obstacle course. I could scarcely approach the block without having to climb, leap and swing my way from one end to the other. This course helped me recoup my energy on the way back from school, it dared me to challenge myself, it gave new pathways to my imagination – I was traversing starship surfaces one day, vaulting classic lava reservoirs the next – and it was ideal for racing against my friends who were, naturally, less familiar with the nuances of the course than I was. This was a space where past and present fused remarkably. The previous function of warehouses adapted not only to the new function of distinctive store and gallery fronts, but also to the shape of a person’s daily life. Even back then, I could feel that my neighborhood, my home, was unlike any other in New York, maybe in the world.

The many snowy winters of the late 70s and early 80s would temporarily rob me of my obstacle course training. The obstacles gave way to impossibly high mountains of snow lining the sidewalks. Did they seem that large because I was small? Did all of New York have mountains that high? The strikes and benign neglect of the 1970s had certainly left no shortage of towering garbage mounds that could serve as the inner structure of snow mountains. Maybe SoHo’s seemed the highest to me because of my incorrigible uncle and a winter night’s poker game.

On Monday nights, my father would host a weekly poker game around a table set up in the back of his huge, echoing gallery. There were a few artists and local business owners on hand, but the regular players were mostly recruited by my mother’s brother, Uncle Billy, an inveterate poker player. Consequently, most of them worked in the same field he did: dental surgery and orthodontics. This regular game, incidentally, was immortalized in the movie Rounders, when Edward Norton tells Matt Damon that he’s going to get a hand in one of the well-known local games, among them the “Dentists’ Game.” Before they got down to playing, my uncle and his pals would join my parents and me for dinner at John Leon’s Spring Street Bar (where Ellen Barkin, later a notable actress, waited tables). Good-natured ribbing and hijinks were common around the table, Uncle Billy the uncontested master.

One snowy winter night, I figured to do my part. Making sure to exit first, I was waiting when my uncle emerged, and proceeded to pelt him with snowballs. Not one to shy away from a (gentle) wrestling match, he fought his way through the barrage and got his hands on me, hefting me high and placing me on an icy ledge of one of those towering snow mountains. Cackling, he hurried off to the gallery, assuming – or perhaps not – that I could simply slide down. But, in fact, it was far too steep and far too high for that. Gasping with laughter and shaking my fist at his back, I found myself quite trapped. My mother had to borrow a chair from the restaurant to stand on and help me down. I’ve never looked at snow mountains the same way again, though they have never looked quite so big to me since that night.

I graduated from Elisabeth Irwin High School (Little Red School House’s upper school) in 1987, and then traveled far afield to New York University, six entire blocks over to the northwest. My hunger for distance from the neighborhood had not sharpened at all, by the time I moved to another floor of my parents’ building at 380 West Broadway in 1991, where I even spent the first few years of my marriage. I did finally leave SoHo (barely – my apartment on Bleecker Street between Sullivan and MacDougal was in the neighboring Greenwich Village) in 2000 and even now still live close by, on Sixth Avenue between Bleecker and Minetta Lane. SoHo had already changed considerably by the time I left in 2000. There were fewer daily amenities for locals available — the only deli on West Broadway was gone by then, as was the only Chinese restaurant in the entire neighborhood (until Pinch showed up, anyway). I return weekly – if not more often – to visit my mother, who still lives in the same loft I grew up in.

Though the facades of SoHo buildings remain recognizable, I see parts of the neighborhood’s industrial heritage shaved away in ever-larger parts. There are fewer raised stairways, sunken basement entrances, loading docks – my beloved obstacle course has all but vanished (though my nephew Ike still plays on the same bars my sister is using in the photo). SoHo’s heritage is harder to make out, its identity somewhat obscured if you don’t know just where – or maybe how – to look. Its gestalt has shifted, the energy coursing through its people and places is less about the arts – creation, invention, re-envisioning – than it is about commercial pursuits. Now, commercial concerns were not foreign to the arts, of course, but the commercial spaces that dominate the neighborhood now have created a different clientele than the galleries that preceded them, the rents have created different inhabitants, both residential and commercial. The population and the neighborhood change together, just as they did when the arts community I was a part of replaced the industrial workforce that came before us. That is what happens to neighborhoods, after all. Which is simply to say that SoHo has gone through the evolution that nearly every spot in New York – every inhabited space in the world – has gone through, and that I’m just some cranky old guy who thinks everything was better before, i.e. when I lived there. That said, it is hard to imagine future generations looking back on this current SoHo as historically significant and as culturally vibrant as the SoHo of the 70s-80s.

SoHo defined my aesthetic sensibility – industrial imagery and industrial decay have always felt mysterious, magnetic and strangely comforting to me. SoHo gave me an appreciation of the layers of history we’re all living upon, both in a city and in a family. And, as a child, it made me feel special. As my horizons expanded, though, I came to see that Manhattan is a collection of distinctive parts. Each one has its own nature, its own character and history, but must ultimately fit together into a viable whole, just as SoHo’s past and present came together into something grand and meaningful.

Jesse Karp is a teacher and librarian at LREI – Little Red School House and Elisabeth Irwin High School, an independent school in Greenwich Village. He is also an author and reviewer. More information is available at his website, beyondwhereyoustand.com.

(marquee photo: West Broadway looking south from Houston Street, ca. 1975, by Bob Weinreb)