by Joyce Romano

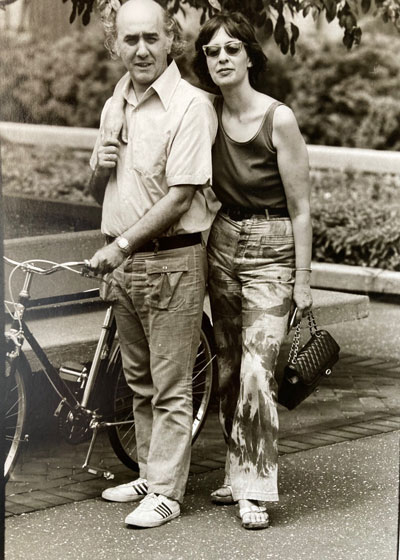

Growing up in the “art world” as an only child of the writer and art critic Corinne Robins and the sculptor Sal Romano, I spent my childhood in museums and galleries and in Washington Square Park. My father was a traditional Italian, but he considered himself an Italian American, and made fantastically huge floating sculptures that he would show at the Max Hutchinson Gallery on Green Street. My mother wrote art and book reviews for various places, like Arts Magazine, The Times, and the American Book Review.

I remember leaving the dimly lit loft on 679 Broadway. I see myself running up and down the loft, running back-and-forth from one end to the other. We are in a hurry because we felt the building shake. It had been a normal afternoon until that happened. We have to get out of the house my mother yells. My mother, a relatively tall and thin high-strung woman with dark hair, finally finds her pocketbook so we can leave the house. As we exit through the doorway into the fluorescent light, the thick brown metal door closes behind us and we go down the stairs. I remember the sound my clogs made on the sheets of metal nailed into the wooden steps. I hang on to the banister leaning against the bright yellow wall, and the three of us go down the stairs as quickly and carefully as possible for an eight-year-old in clogs with a terrified dog and a mother with vertigo; we went down the stairs and ran out on the sidewalk.

After the Broadway Central hotel (on 673 Broadway, three doors down from us) collapsed, our building was condemned. It took a building falling to get my father to leave his sculpture studio, one floor below our loft, and make the best investment of his life.

When we moved to the new neighborhood Soho, it felt desolate, nothing but empty streets with grey-green cobblestones that looked brown in the rain. The large factory buildings that had seen better days looked out on nothingness when the lights went out. The nights were quiet until early morning when the calamity of trucks bellowed down the stone streets, echoing in the hollow darkness. They were the night monsters, their metal doors making enormous sounds when they rolled up, and the loading ramps came crashing down waiting to unload. Metal has a particular pitch when it hits the stone. Most of the trucks were gone when we would leave the house in the morning and walk down Wooster Street to the Prince Street subway station. We passed by the construction workers with their yellow hats and busy tool belts slung across their hip like cowboys; all sitting on the loading platforms having coffee in white Styrofoam cups before they were impeached. They whistled as we walked by commenting on our German shepherd collie dog who was dressed up in an outfit, I had wrangled her in that morning, maybe an old T-shirt and a skirt. Being an only child, one did what one had to do to make friends even if it was the dog.

We had art magazines in the house because my mother was entitled to them working for the Press. She was a compulsive reader who never left home without at least two books in her bag. My mother was especially dedicated to writing about women and black artists. My father was doing monumental water sculpture back then and spoke Italian when he was angry. My father was a passionate man, he was very concerned with closing the blinds and buying curtains so the neighbors couldn’t see in. It was 1973 in Soho; we had no neighbors.

A few years later, we noticed the area slowly becoming inhabited by other artists and eventually by art galleries. Along with art came food. It was so exciting when the Asian fruit and vegetable market opened down the block from us with all its loud colored flowers spilling out on the sidewalk. The only store I remember before that was a small deli two blocks away on the corner of Prince and West Broadway that always looked a little dirty but sold individual pieces of bazooka bubble gum, so it was a hotspot for the kids. Prince Street always looked better than the rest of the blocks because people took care of their store fronts. A small cheese shop that we knew as “Giorgio’s” opened, it was painted hunter green on the outside and in the window was a museum of different cheeses. Flat, and triangular or round and thick, marvelous chunks of expensive cheese. Diagonally across the street from the cheese shop was a restaurant called FOOD with big windows framed in black trim that wrapped around the corner of Wooster and Prince Street. It served healthy food, cafeteria style, and the employees wore clogs. More galleries opened, and more people came, and more stores, and the more stores, the more restaurants to feed the people that came to shop. Those are some of my early memories of Soho. That Soho is now another world, one I recognize once in a while.