Last month I had the privilege of interviewing Lorenza Giovanelli and Matthias Koddenberg of the Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation. Still in its planning stages, Lorenza and Matthias gave me a hint about what’s ahead for the Foundation and the SoHo building where it will be headquartered. They also shared insights into Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s relationship with their adopted home, as well as their own memories of the famed couple and their live-work space.

Christo Vladimirov Javacheff (1935–2020) and Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon (1935–2009), the artists referred to as “Christo and Jeanne-Claude,” were such equal partners in the work they created that they are known as a single unit. As many of you know, they lived and worked in SoHo at 48 Howard Street for over 50 years. They are known as creators of spectacular, large-scale, site-specific works including the Wrapped Reichstag, The Pont Neuf Wrapped, Running Fence, and of course The Gates in Central Park. What is less known is that these world-renowned works all originated in a SoHo loft building made habitable through sweat equity and a few dumpster diving trips on big garbage night.

When I visited The Gates in 2005, I remember feeling a kind of elation and love for New York City that I haven’t really felt since. Walking through each gate draped in saffron fabric brought memories of my Japanese grandmother, who used to lead me through the vermillion gates of Shinto shrines, to which the title of the installation alludes. Looking up, I glimpsed the skyscrapers of Central Park South and beyond. Past and present melded, and I felt very much at home. At the time, I had no idea that this beautiful, ephemeral work of art had been conceived, designed, and planned mere blocks from my home on Mercer Street in an unassuming industrial building at 48 Howard Street.

I now know that “48 Howard” is an address, a home, a state of mind. The spoken and written words of Lorenza, Matthias, Christo, and Jeanne-Claude, tell the story of what the Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation seeks to preserve: a venerable artistic legacy, including the building that nourished it.

Lorenza on the future of the Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation:

We’re still developing a plan for the future use of the building; however, we would like to preserve what 48 Howard street is now, because everything was built and designed by Christo and Jeanne-Claude. The entire building is a sort of time capsule, it’s somehow part of the archive. We really feel like we should do our best to make as little changes as possible because the moment you step in, you really realize how they lived and worked, and it tells you a lot about what they created together. [We intend] to keep this building alive, perhaps turning it into a sort of cultural hub that will speak about Christo and Jeanne-Claude and this neighborhood, and the connections that they had and they built.

The idea is to foster curiosity so that people could learn more about Christo and Jeanne-Claude, their art, and how they influenced and impacted other artists and other generations of artists. I would also love to maintain both the studio and the apartment as they are, or eventually revert them to their sixties look, when Christo and Jeanne-Claude moved here. Having access to these spaces would allow people to learn more about the context of their work and their life when they moved into the city. So that’s my vision. I know it’s a big dream, but I’m sure it’s not impossible. I think that for research purposes, being able to access an artist studio that is flawlessly preserved is every art historian’s dream. (Interview with SoHo Memory Project, February 15, 2024)

Jeanne-Claude on moving to NYC:

When we came to New York, we looked for a place to stay. We visited maybe fifty, sixty places. They were all too small, too expensive, or too horrible. Then Claes Oldenburg told us to visit the factory building in SoHo where he had his former studio that he used merely to store things. There were no other tenants and we rented two floors at 70 dollars each. It was all filthy and full of machines and dirt. There was oil all over the floor, and some of the ceiling was down. It took us months to repair and clean up everything. (Christo and Jeanne-Claude in/out studio, p.131)

Matthias on 48 Howard then and now:

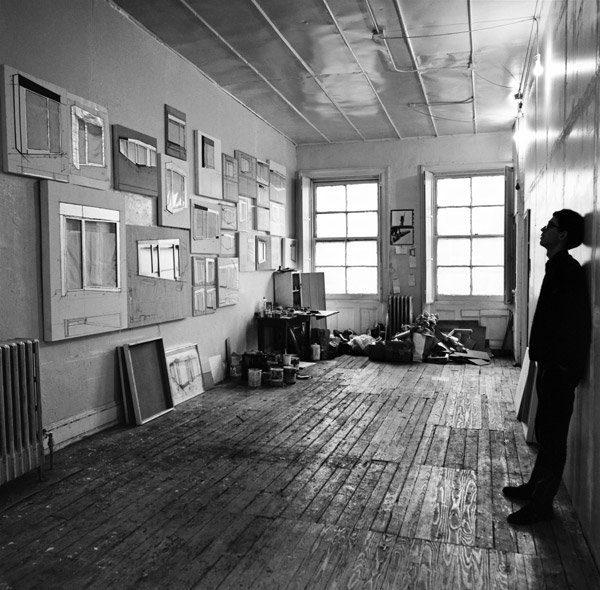

Nothing much has changed in Christo’s studio since they moved here in 1964—apart from the plaster that is slowly crumbling. When he and Jeanne-Claude moved here fifty years ago, the 19th-century building in the middle of Manhattan had been unoccupied since the 1940s. They added walls, filled in holes in floors and ceilings, repaired and painted everything with their own hands. Philip Glass and Gene Highstein installed the bathroom and Gordon Matta-Clark built the bedroom closets. The remaining pieces of furniture, which still stand unchanged in their original places today, came from the dump or were made by Christo himself. (Christo and Jeanne-Claude in/out studio, p.7)

Lorenza on furnishing 48 Howard:

“In Manhattan, Thursday and Friday mornings were bulk collection days, so Wednesday and Thursday nights people could legally dump their unwanted oversized furniture,” Jeanne-Claude said, remembering the nights she spent with Christo scavenging SoHo sidewalks and dumpsters, looking for precious abandoned treasures to repurpose as furniture or art materials. One evening they harvested an intact, but slightly burned, wooden desk. The next night they spotted an abandoned wooden chair on the sidewalk. When Jeanne-Claude approached it, Christo, still shy about foraging, crossed the street, pretending not to know her. A little sanding and some gray paint transformed these into a matching desk and chair that would become family fixtures. Both perfectly well preserved, the gray patina hardly eroded by time, they occupy the same corner where the adventurous couple originally placed them. (“48 Howard,” Cahiers d’Art Christo, p.152)

Christo on his studio as a refuge:

The studio is the only place where I can be alone. The moment I leave my studio, I’m confronted by consultants, engineers, specialists, politicians, farmers, cowboys and presidents. It is only in the studio that I’m really alone with my idea. It is the place where I feel comfortable, where I’m happy. My drawings and collages, incidentally, are also the only things that encourage me in my belief that a project will succeed, because Jeanne-Claude and I have often gone through hard times when a project was not progressing or had been rejected. Whenever that happens I go into my studio and look at the sketches. They help me continue to believe in our dreams. They keep my fire burning. (Christo and Jeanne-Claude in/out studio, p.12)

Lorenza on Christo’s studio:

The colorful noise of the city is reduced to a muffled hum, and it is there in that silence you are able to hear and sense the balance of a microcosm built by sediment—grown, matured, and aged together with its creator. Objects too have absorbed the personality and learned the language: a most faithful portrait, a human archeology, conducted through the experience of a space that embodies the absolute perfection of creative syncretism. Here is an almost symbiotic existence of content and container, whose intimate relationship does not simply generate a collection of souvenirs from the past, but writes the pages of an untold story. (“48 Howard,” Cahiers d’Art Christo, p.156)

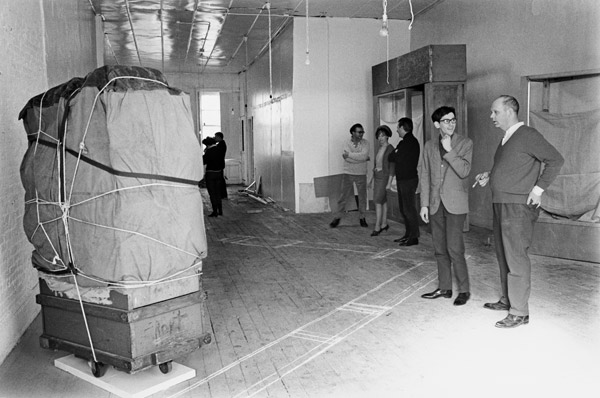

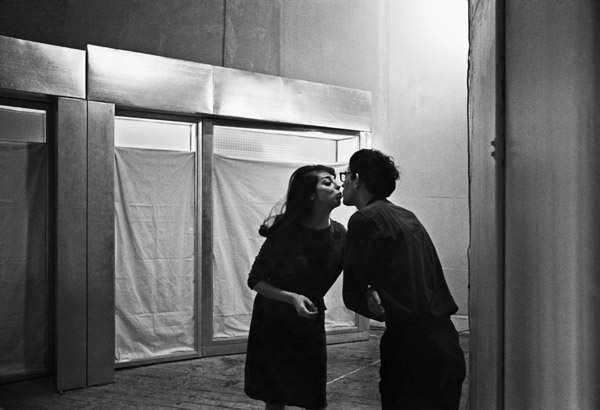

Matthias on 48 Howard as a social hub:

When they moved to New York in ’64, Christo and Jeanne-Claude hardly knew anyone, so they had to start from scratch. And of course they had to make connections with all kinds of people, other artists, dealers, galleries, collectors, museums. So Christo and Jeanne-Claude would have regular parties and dinners on Howard Street, for which they had a huge table that is still there. They would gather around the table and Jeanne-Claude would cook. In fact, it’s kind of legendary that she made terrible food, but she was unparalleled in her ability to bring people together. Howard Street was really a hot spot at the time. All the leading artists, critics, and curators would regularly come to Howard Street and spend time there. Connecting with these people was a huge factor in their success, because that’s how they found collectors, that’s how they established themselves as artists. (Interview with SoHo Memory Project, February 15, 2024)

Lorenza on memory and what New York City meant to Christo and Jeanne-Claude:

It was not just a matter of migrating to the United States of America. It was a matter of going to New York because New York was the place to be and the place where people could actually make their dreams come true. I think that if Christo and Jeanne-Claude didn’t move to New York, they would’ve never achieved what they actually did because this city gave them such great inspiration, and put them in contact with so many different people, opening up their minds in a way that probably Paris could have never done.

The Gates is the ultimate homage to their lifelong love story with the city and a capstone in their career because since Christo and Jeanne-Claude moved here, they envisioned several projects for this very city, but none of them eventually landed other than The Gates. So I think that tells you a lot about how deeply they loved New York, and how they really wanted to gift their city with something of their own. And they eventually succeeded 40 years after they moved here. It was spectacular. Yeah, that’s what I think New York was to them, a creative nest. That’s why Christo wanted this building to continue being the headquarters of the foundation, because they created something here together.

I remember very well that he told me just a few days before he passed away, “Just make sure that people won’t forget what we did here.” So memory was really important to him, and memory is actually the essential element of all their projects. Being temporary, they continue to live in our memories. …After they disappear, they’re made of memories. So memory to us is synonymous with legacy. (Interview with SoHo Memory Project, February 15, 2024)

Matthias on the aura of 48 Howard:

When I think of Christo and Jeanne-Claude, I cannot help but think of the building that was their home for 56 years. The Howard Street building, such an integral part of their art and their life. The smell of it: Jeanne-Claude’s perfume, which the house continued to exude from its every pore, even after her death. The sounds of it: the Mozart CD that stayed on repeat mode to the despair of any visitor after the fifth time around, the squeak of the old wooden staircase that Christo, Jeanne-Claude and countless guests, friends and collectors continually clambered up and hurtled down through the years. “Five floors! No lift!” How many times did I hear those words, always spoken with a mixture of pride, loyalism and a touch of mischievous jubilation with regard to visitors unaccustomed to getting around on foot! I feel that 48 Howard Street is surrounded by an aura that no other building possesses. (“The Subtenants of 48 Howard Street,” Unwrapped: The Hidden World of Jeanne-Claude and Christo, p.28)

Lorenza on the essence of 48 Howard:

48 Howard is the first chapter of a story where a man and a woman joined their hands and, without ever letting them go, gave the world unique and unrepeatable instances of beauty. It is the place where you can still hear their hearts beating in unison. (“48 Howard,” Cahiers d’Art Christo, p.157)

Lorenza Giovanelli (*1990) studied History of Art at the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore in Milan (Italy). In 2016, she was the office manager of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s outdoor temporary art installation The Floating Piers. Since 2017, she has worked at Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s home and studio in New York as collection and exhibition manager. Today she serves on the board of directors of the Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation, committed to fostering public knowledge and appreciation for Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s life, pioneering work, and artistic and cultural influence so they may continue to be an inspiration for generations to come.

Matthias Koddenberg (*1984) studied art history at the Universities of Münster (DE) and Zurich (CH). He works as a writer, editor, and curator; his publications include texts and books on modern and contemporary art. A close friend of Christo and Jeanne-Claude for over 20 years, he has been a member of their “working family” and a frequent visitor to 48 Howard Street. His book Christo and Jeanne-Claude: In/Out Studio, published in 2021, was the first major publication on the artists’ work since Christo’s death in May 2020. Today, he continues to serve as an advisor to the Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation and is part of the team that keeps their legacy alive.

Publications referenced in this story:

Christo (2020). Editions Cahiers d’Art.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude: In/Out Studio (2015). Verlag Kettler; D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers.

Unwrapped: The Hidden World of Christo and Jeanne-Claude (2021). Sotheby’s.

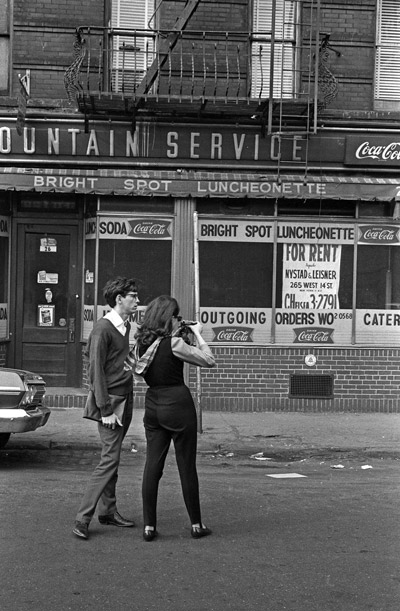

Top image: New York, 1967: Jeanne-Claude, their son Cyril, Christo, and Christo’s father Vladimir Yavachev in Christo’s studio. Photo: Ferdinand Boesch