Before 1971, SoHo artists, almost all of whom also lived in their work spaces, were living here illegally. For a while, no one seemed to notice or care, the city pretty much looked the other way, but when non-artists looking for investment opportunities began noticing the profit potential of such spaces, artists, who, until then, chose to remain anonymous and hidden, came together to form the SoHo Tenants’ Association and then incorporated as The SoHo Artists Association (SAA), initially in order to legalize loft dwellings and fight to keep SoHo an affordable place for artists to work. Without the community organization and activism of residents, SoHo most certainly would not have evolved as it did. It would most likely have been taken over by either real estate developers looking to make a quick buck or the city looking to build new housing projects, or both. Luckily, the SAA and other groups willing to put in time and labor stepped up and fought for what they felt was rightly theirs.

On January 20, 1971, the City Planning Commission voted 4 to 0 to recommend to the Board of Estimate that artists be permitted to reside in the manufacturing buildings of SoHo. On January 28, the Board of Estimate made that recommendation law. This law was ultimately passed due to the SAA’s two-year battle with the city for the legalization of loft living in SoHo and set a precedent for how other neighborhoods and cities would approach adaptive reuse of non-residential urban areas.

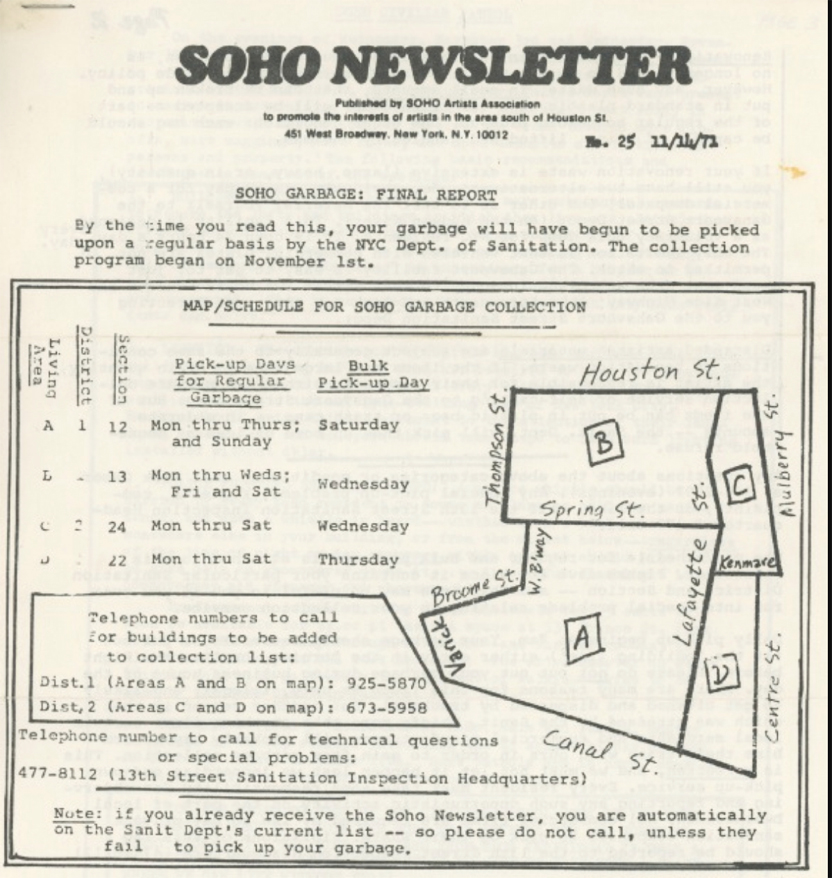

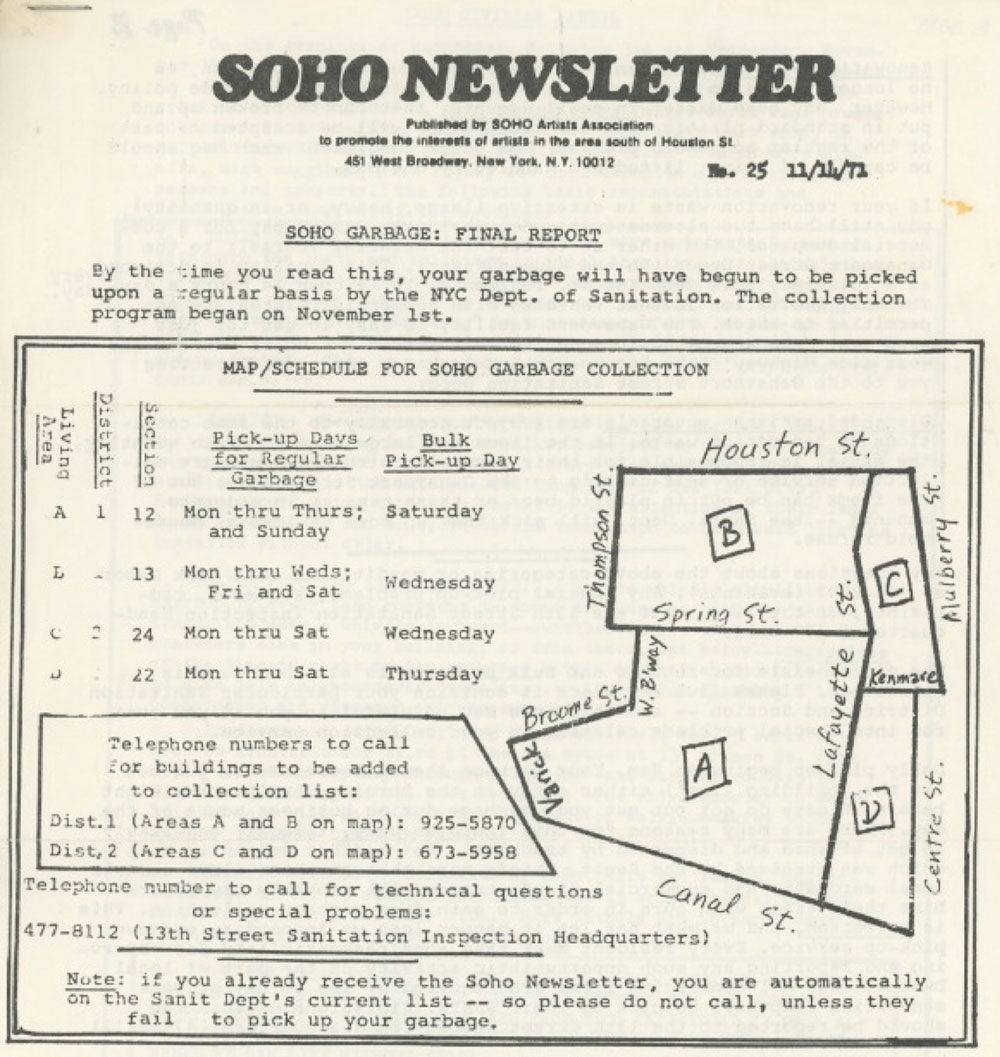

A copy of the SoHo Newsletter, published by the SAA, from November 14, 1972 that outlines newly instituted sanitation services

Another everyday “amenity” people in any other neighborhood would have considered a given that the SAA succeeded in bringing to SoHo weas trash removal. By late-1972, after it was public record that artists were not just working but living in SoHo, the SAA met with representatives of the Department of Sanitation to begin regular curbside pickup of household and bulk garbage. Prior to legalization, residents had to find ways to dispose of their own trash, mainly by depositing it in public trash bins, making sure nothing in the bags could trace the refuse back to them, such as mail or banking information, was legible. This proved to be inconvenient at best and more often a smelly nightmare sitting in the kitchen until the opportune moment presented itself to either search for a corner trash can or to sneak one’s trash into a commercial trash pile, as commercial firms were (and still are) required by law to hire private carting services. Once residential trash pickups were instituted, the tables turned, and loft dwellers needed to be extra vigilant to make sure commercial tenants did not sneak their trash into the residential trash, thus jeopardizing their newly-won public sanitation services.

By the early-1970’s, the fourth precinct, which included SoHo, had a dramatic rise in the number of murders, rapes, break-ins, and hold-ups. Concerned about their community’s safety, the SAA took it upon themselves to beef up neighborhood security by educating people about self-defense, providing whistles, lobbying for better lighting in public areas, and, most importantly, organizing patrols of the neighborhood. Many of the crimes took place in the early evening, just after working hours, so some residents suspected that local factory workers may have taken advantage of their familiarity with the comings and goings of the artists who shared their buildings, and had taken advantage of them. The SAA was determined to change the perception that the artists were passive, non-violent, and isolated, and organized foot patrols to protect their neighborhood. In the end, the patrols only lasted a few months, but this was enough to deter would-be attackers, as the number of crimes in the neighborhood dropped.

Through the SAA, as well as efforts of smaller resident groups (not everyone in SoHo was a member of the SAA, nor did they unanimously support its causes) and even individuals (one Greene Street resident alone was responsible for foiling dozens of car thefts), the residents of SoHo filled the gap that would have customarily been filled by municipal workers. Artists moved to SoHo, for the most part, to be left alone to create and work in peace, but were forced by circumstance to make themselves seen and band together. Community-building is an ongoing, open-ended struggle. Sadly, many of those who put themselves out there and fought the good fight were eventually forced out of the neighborhood, by either necessity or choice, before they could enjoy the rights they earned through their valiant efforts. We all know what eventually happened as time went on and market forces took over, but for a short time, flowers were able to grow in the urban wilderness. Although SoHo has changed almost unrecognizably over the past decades, I nonetheless feel lucky to still be here and salute those who came before me.